Read Varied & Complex Texts

SECRET SITE

Recognize the value in raising rigor

The college and career-ready standards outline the expectations for varied and complex texts (Common Core State Standards).

Kristina shared many statistics about students’ inability to handle complex text. Each of the expert quotes and/or statistics cited in this download are attributed to their original source.

Two professional must-reads include Text Complexity: Raising Rigor in Reading and Rigorous Reading: 5 Access Points for Comprehending Complex Texts.

Although close/analytic reading was initially a middle school, high school, and college-level reading skill, it is appropriate for the elementary classroom with some modifications. Read “Close Reading in Elementary Schools” by leading experts Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey.

Leading experts on close reading, Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey, have dozens of classroom videos posted on YouTube. There are numerous close-reading lessons recorded in a variety of grade levels and content areas.

K-1 teachers will love the close-reading lesson ideas created by Amanda Zanbelli & Aylin Claahsen. (Complete lessons available for purchase on Teachers Pay Teachers.)

You don’t read everything closely. There are different reads for different needs. There should be times we push students to grow with harder texts, and times that we work to throw a larger quantity of texts that are easier to read. This can be explained with two analogies:

- The marathon analogy identifies days to push and grow versus days to recover and take it easy. The marathon analogy also reminds us that every day or every week is not harder than the previous one. It’s not a constant crescendo, but a spiral of experiences where we grow with hard texts and recover with easier texts.

- The weightlifter icons reiterate that simply exercising without adding weight doesn’t increase muscles. This gets at the heard of differentiation; we can’t differentiate all the time. There have to be instances when we make the reading experiences more challenging to increase our students’ reading muscles.

Introduce Close Reading to Students

Prepare students for the fact that there will be days you will read hard, complex text and days you will read simpler, just-right text. Tell them that this is normal–this is what readers do.

For the complex text, they will need to read it multiple times, gaining a deeper understanding of author ideas with each reading.

- Reveal the eyeglasses icon. Initially, readers comprehend on a surface level. They read to paraphrase/retell specific details, summarize the important concepts, and determine the main ideas.

- Reveal the microscope icon. During a closer look, readers zoom in to analyze the text and evaluate author decisions about word choice, organization, and purpose.

- Reveal the telescope icon. With a deeper comprehension of the text, readers zoom out and integrate new understanding from the text with other texts and bigger ideas.

After discussing each of the different reading purposes per phase, bring it all together. Introduce them to the process or framework of close reading and its three phases.

- Use this mini-poster to connect the Thinking Voice thoughts to the phases of close reading.

- You could utilize the “Readers persevere through difficult text” PPT.

- The 3 phases of close reading are also to be applied to solving story problems in math.

- Incorporate the close-reading triggers into your text-based discussions.

STEP 1: Select a complex text

VARY TEXT COMPLEXITY.

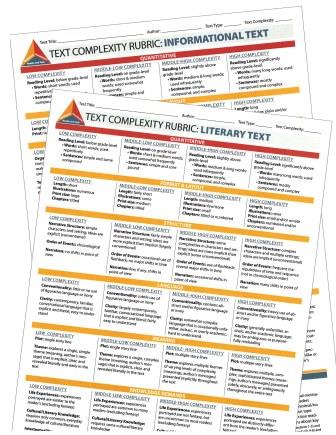

Since teachers are to determine text complexity themselves, an assessment tool is essential. Kristina built text complexity rubrics for Literature and Informational Text that measure all three factors of Text Complexity.

Text complexity can also be determined with other quantitative measurements besides Lexile levels. Use this Text-Level Correlation Chart to determine how measurements across different scales are aligned.

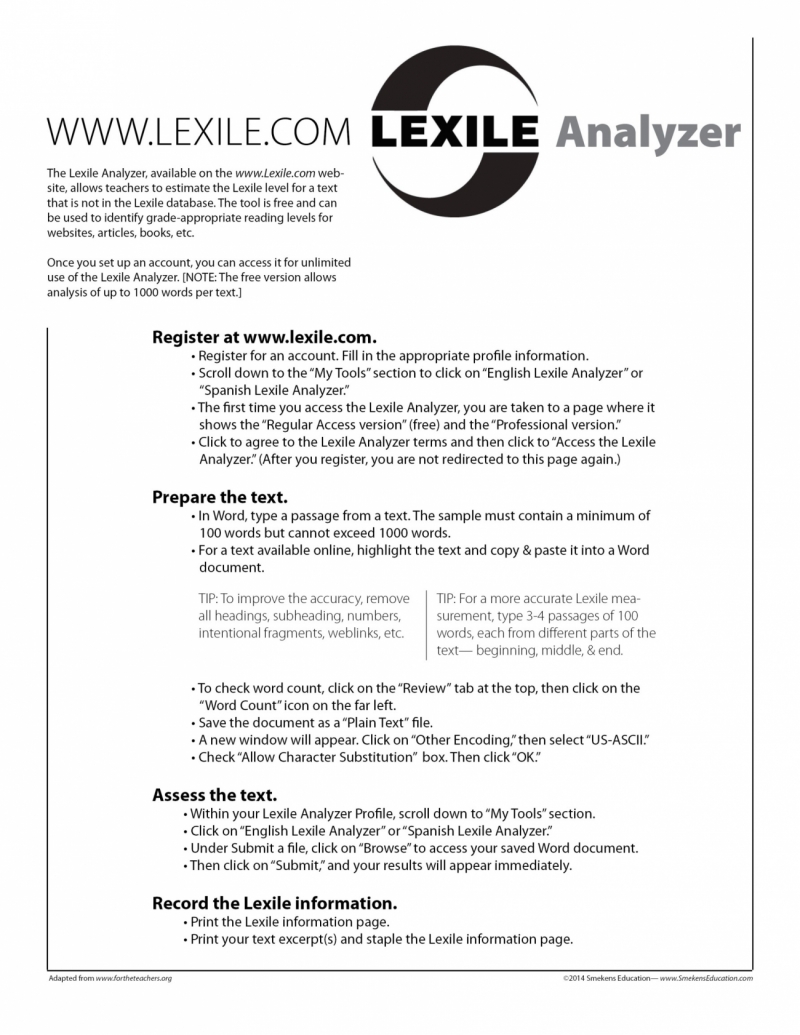

If you do not know the Lexile level of a text, check out www.Lexile.com or Book Wizard to see if it’s already been determined. (NOTE: Book Wizard allows you to select DRA, Guided Reading, or Lexile options.)

If the text doesn’t appear in either of these sites, then follow the steps outlined in the Lexile Analyzer document. Teachers can estimate the Lexile level for an English or Spanish text that is not in the Lexile database. The tool is free and can be used to identify grade-appropriate reading levels for websites, articles, passages, books, etc.

Utilize Appendix A (pp2-22) and Appendix B within the CCSS for text complexity examples. NOTE: These are NOT required reading lists per grade level.

VARY READING EXPERIENCES.

- Slim the text (and make it move faster) by showing small portions of the movie version of a book in lieu of reading every word aloud in class. Identify the page number of the text that the movie clip will cover and discuss the reading/viewing purpose. Check out some of these examples. Download the Now Playing editable template in PowerPoint.

You’ll want to screen new chapter book titles. Common Sense Media offers a great site for screening books/movies for content appropriateness (language, violence, etc.). It includes age-level recommendations as well as content-specific spoiler alerts.

BUILD BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE WITH TEXT SETS.

Rather than pre-reading and frontloading through lecture, prepare students for complex texts on unfamiliar concepts through the reading of a Text Set. Layer their background knowledge and introduce essential vocabulary with shorter texts they can more easily access. This prepares them for the knowledge demands of the more complex text you will tackle next.

- Check out this Learning Center article on more strategies to build background knowledge without pre-reading.

- For a list of picture books sorted by content-area themes and concepts, you’ll love Lester Laminack’s book Reading Aloud Across the Curriculum. It’s a book of books!

- Scholastic is putting together text sets for grade levels that center on major content-area units.

- Mary Ann Cappiello, author of Teaching with Text Sets, has an entire blog about creating text sets.

- Access online newspaper articles organized by subject/concept at New York Times for the Classroom, ProCon.org, and Newsela.com.

In addition to building background knowledge, reading multiple texts allows students to make connections and comparisons across texts. This honors the multi-text expectation outlined in the Standards (Common Core version, Indiana version).

STEP 2: Draft text-dependent questions

Develop effective questions that require students to delve into a text to find answers.

Kristina revealed several close-reading lesson-planning tools, depending on your available technology and personal style.

- Smekens Education has put together a Close-Reading Questions set that includes both literature and information text (also sold separately: Information Text / Literature).

- Single-page text-dependent planner (PDF version/Word version)

- 2-page question planner, with prompts & cues (PDF version/Word version)

Another technique would be to color-code your Thinking-Voice questions per reading/phase.

- PHASE-1 QUESTIONS—blue

- PHASE-2 QUESTIONS—green

- PHASE-3 QUESTIONS—red

Access passages and corresponding text-dependent questions for the following:

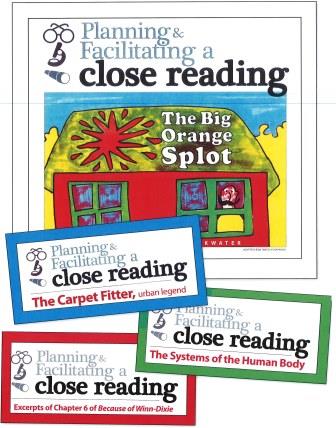

- The Big Orange Splot—primary literature

- Because of Winn-Dixie, chapter-book excerpt

- “Carpet Fitter”—urban legend (revised version)

- “Body Systems”—textbook passage

- “Let it Go” original lyrics from Disney movie Frozen.

- “Let it Go” lyrics from Granger Community Church Mother’s Day performance.

- The step-by-step lesson plan Kristina executed during the workshop.

STEP 3: Establish reading & annotation purposes

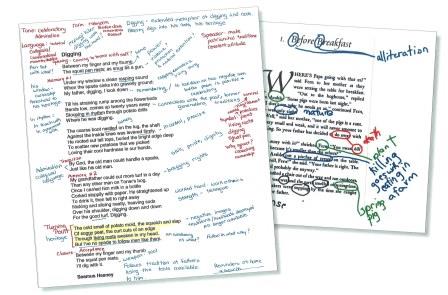

Annotation is a note of any form made while reading a text. It slows down the reader in order to deepen understanding.

Teach students a single annotation skill, one at a time.

- Scaffold annotation skills to be taught at each grade range. (Access a PDF and student bookmarks.)

- Check out www.newsela.com for a free website to practice why-lighting.

- Download a series of annotations made by students during close-reading experiences.

- For those working with digital texts, this article will be particularly helpful–“Actually Achieving Close Reading with Digital Tools.”

STEP 4: Support discussion & scaffold thinking

After giving students an opportunity to read (Step 4) and discuss in smaller, more intimate scenarios (e.g., pairs, small groups), facilitate whole-class discussions using this Turn & Talk graphic.

Download a variety of floor plans for structuring text-based conversations. (NOTE: These are some of the ideas Courtney Gordon shared during the 2013 Literacy Retreat.)

- Check out this video of students participating in a whole-class discussion that demonstrates the 4 Talk Moves Kristina mentioned during the workshop.

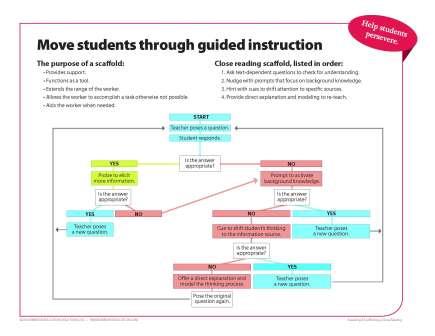

Follow this flowchart of guided instruction. If students answer a question inaccurately or incompletely, then we should guide them toward discovering the correct information–rather than just giving them the answer. For more information on how to prompt and cue students, read “Guiding Learning: Questions, Prompts, and Cues” by Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey.

STEP 5: Reveal the after-reading task

The culminating task after a close reading should relate to the core understanding and key ideas of the text. A coherent sequence of text-dependent questions will scaffold students toward successfully arguing a big idea and supporting it with textual evidence. Such tasks can be oral activities, although most end up with a written product. They can include:

DECISION TASKS–Select the best alternative from many possibilities, using the text to locate evidence for your choice.

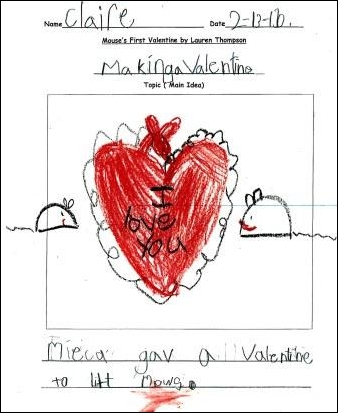

- Primary students might return to their first statements (regarding what the text was about) and make new ones. More than a literal retelling, students can be taught to determine the main idea and even the author’s message/theme. Check out the progression of thinking that Maria Bachuchin walked her kindergartners through after reading Mouse’s First Valentine. (Access a template to try this strategy with your students.)

Anna Parks, ELA teacher at Norwell High School (IN) drafted this after-reading writing task in response to To Kill a Mockingbird. She told the students…Pretend you are the editor of Glencoe/McGraw-Hill. In the mail you received the manuscript for To Kill a Mockingbird from Harper Lee. You’ve read it and now need to write a letter of acceptance or rejection to the author regarding the publication. Your letter should follow the guidelines for formal business letters and include specific evidence from the text to support your decision for or against publishing the manuscript. Read authentic student examples for both a REJECTION and ACCEPTANCE.

PROBLEM TASKS–Resolve conflicting information in order to determine a decision path that will lead to a desired outcome.

Each of the tasks above can be accomplished with a Conversation Roundtable. (Notebook version available.)

- Students use a single corner to note their individual thinking.

- A small group discusses their individual thinking, and, in the other three corners of the handout, listeners can jot down relevant points made by their peers.

- Students resume working independently to draft a written response in the middle, pulling on ideas shared during their roundtable conversation.