Literacy Retreat 2016

SECRET SITE

Introduce readers to the voices in their heads.

Introduce the ways (comprehension strategies) readers think

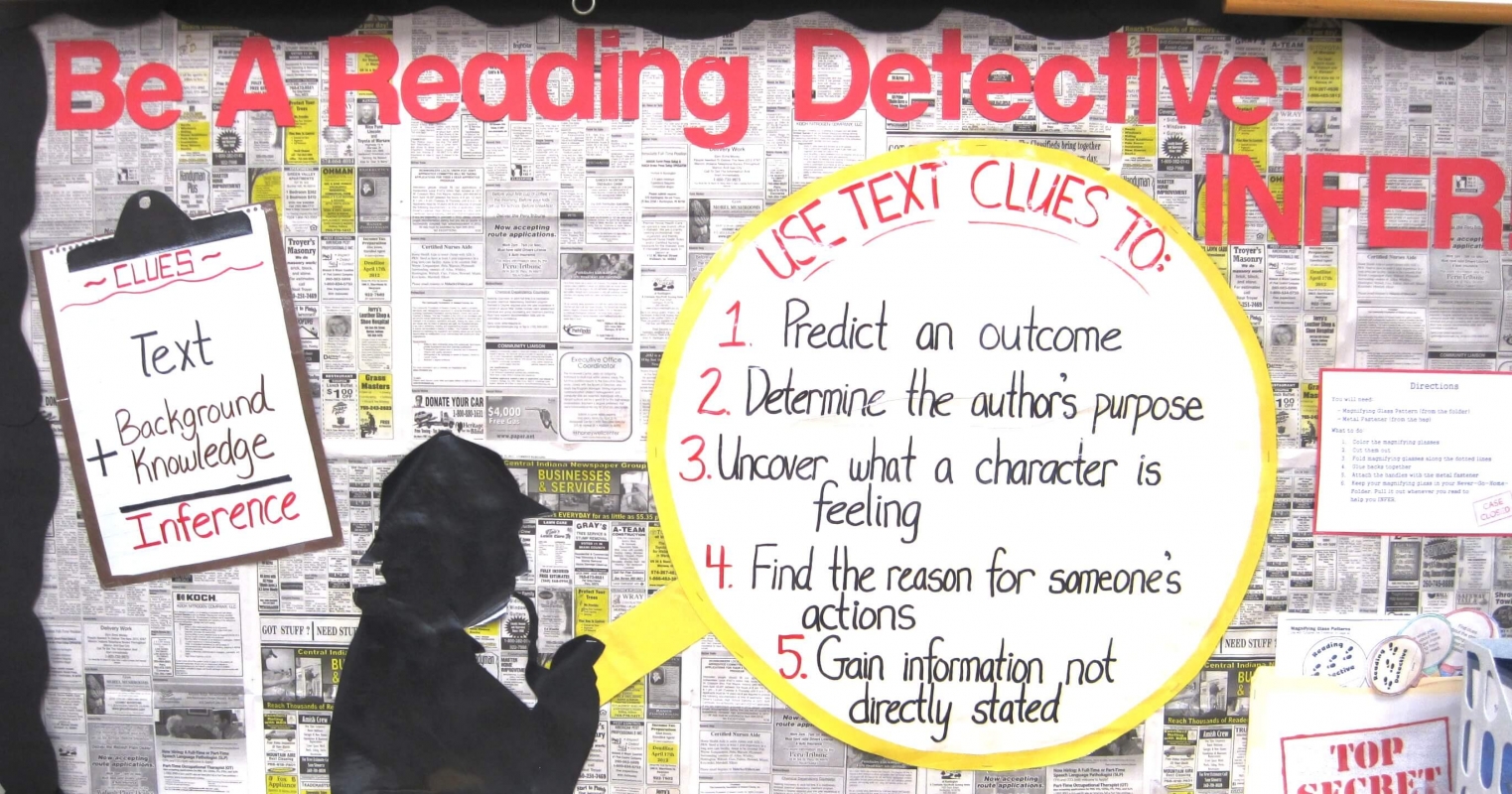

Demystify how to make an inference

Readers look for “patterns” using their reader magnifying glasses.

Guide students’ off-track thinking by bringing in other relevant details. Like Prop Predictions, their inference narrows with each additional prop. (Download a list of suggested props tied to popular texts.)

Set the tone of an evidence-based classroom

Don’t be satisfied with right answers. Push for what is the answer and how do you know.

Remain neutral when students are giving you their inferences. Don’t “give away” if they are right or wrong. Rather, use a line from the Justification Cheat Sheet to ask them to support their thinking.

Readers use the words and details from the text to make inferences. Teach students to collect words about what the text SAYS in order to figure out what it MEANS.

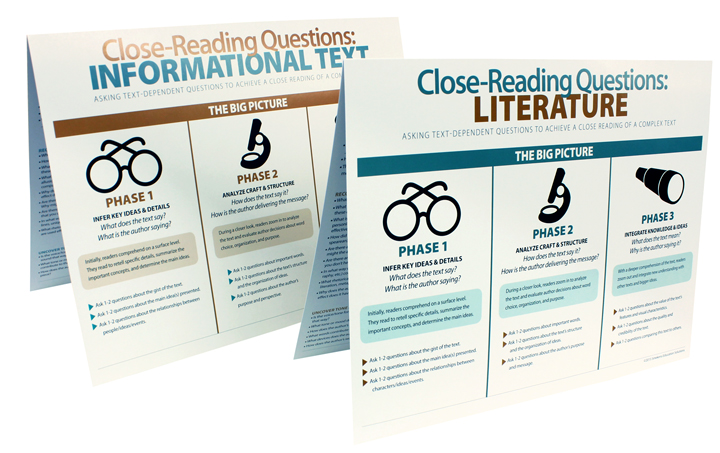

To create an evidence-based classroom, the questions teachers ask must be dependent on the text.

Write the Inference.

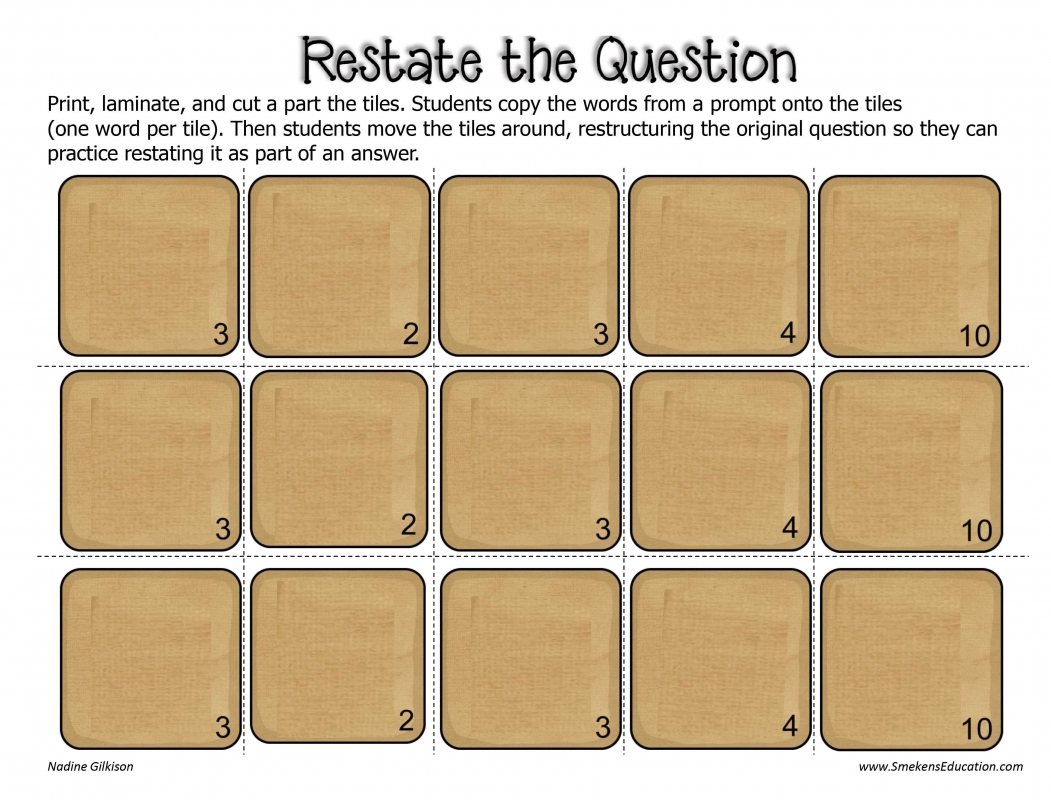

Help students learn how to restate the question using words from the original prompt. Writing words on the Scrabble tiles, students can move them around physically to reword the original prompt.

- Write each word from the original prompt or question on the Scrabble tiles.

- Teach students to recognize key words (differentiating them from those less important). Slide the less important tiles to the side.

- Physically rearrange the “key word” tiles to reword the original prompt into an introductory phrase.

- The PDF version needs to be printed, laminated, and cut into separate tiles. Students use write-on/wipe-off markers during a small-group or station time.

- The Promethean board or Notebook version would be a great all-class lesson tool.

It’s easy to test if a student’s restatement of the question is strong. Simply read the sentence to someone else and see if that person can guess the original question. Inferences that include key words make sense to a listener without him ever knowing the original question/prompt. This is the concept of Invisible Questions.

Don’t ask for evidence until you’ve defined it. Distinguish how it’s different than just any detail in the text.

Customize an Evidence Sort to allow students to practice finding evidence. Provide students a statement/question and several sentences from the text(s). Students sort “evidence” statements from “just details” (editable Word version).

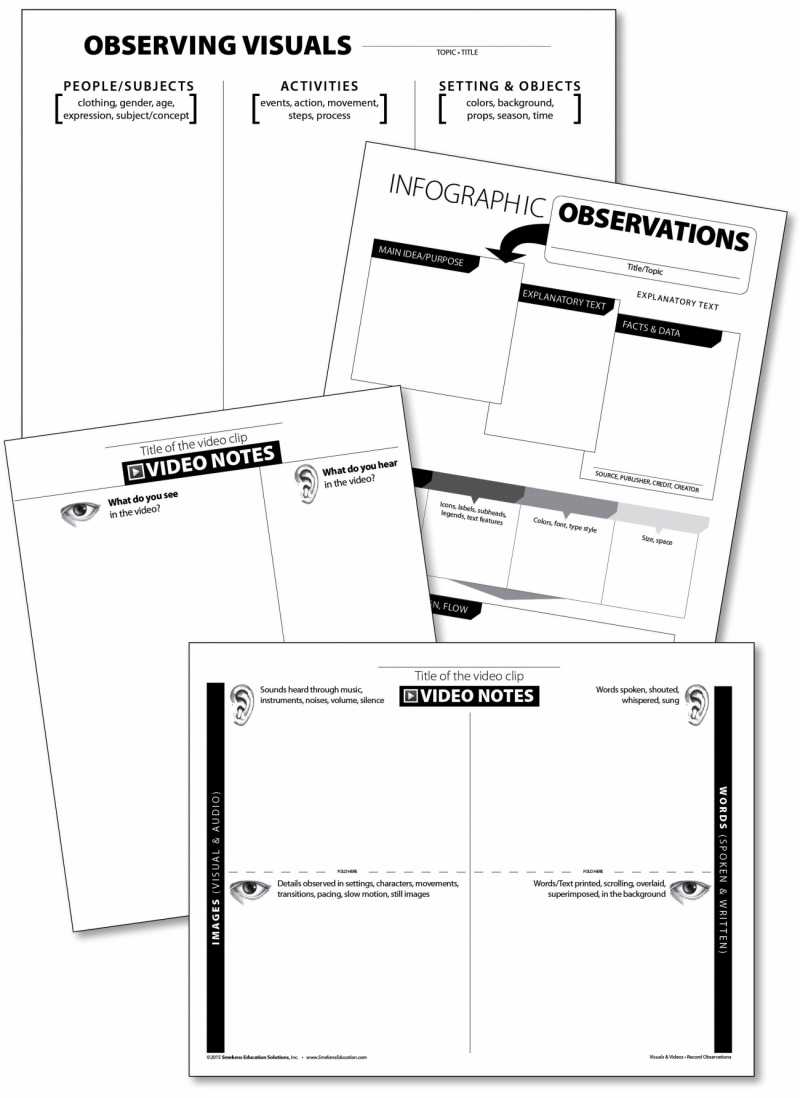

Take time to teach students how to “read” photos, illustrations, and political cartoons. Use a simple note-taking organizer to analyze: people/subjects, action & activity, setting & objects. Here are several examples:

- Park scene (informational photograph)

- Man on Moon (informational text photograph)

- Scaredy Squirrel (picture book illustration)

- Fox (picture book illustration)

- Moby Dick (illustrated novel)

“Read” infographics. Make note of the following facets: main idea/subject, data, source, text/words, visuals, organization.

“Read” video clips/movie excerpts. Use the 2-column T-Chart to note what you see and what you hear.

Apples to Apples. For a quick experience making inferences and citing evidence from visuals, use the Big Picture version of “Apples to Apples.” Reveal a single green card depicting a word and definition and five random images. Students determine which image best depicts the word/definition and write a short constructed response.

- Type time-stamped notes while watching the video on a split screen. VideoNot.es is a fabulous (and free) online app available through Google drive. View these tutorials for how to access it and how it works.

- Read this Idea Library article about two additional apps that support annotations of multimodal texts.

Extract

This is the next step in the process when students need to flip back, scroll up, or look down at the text to find specific words and phrases.

Some questions require multiple details to be extracted.

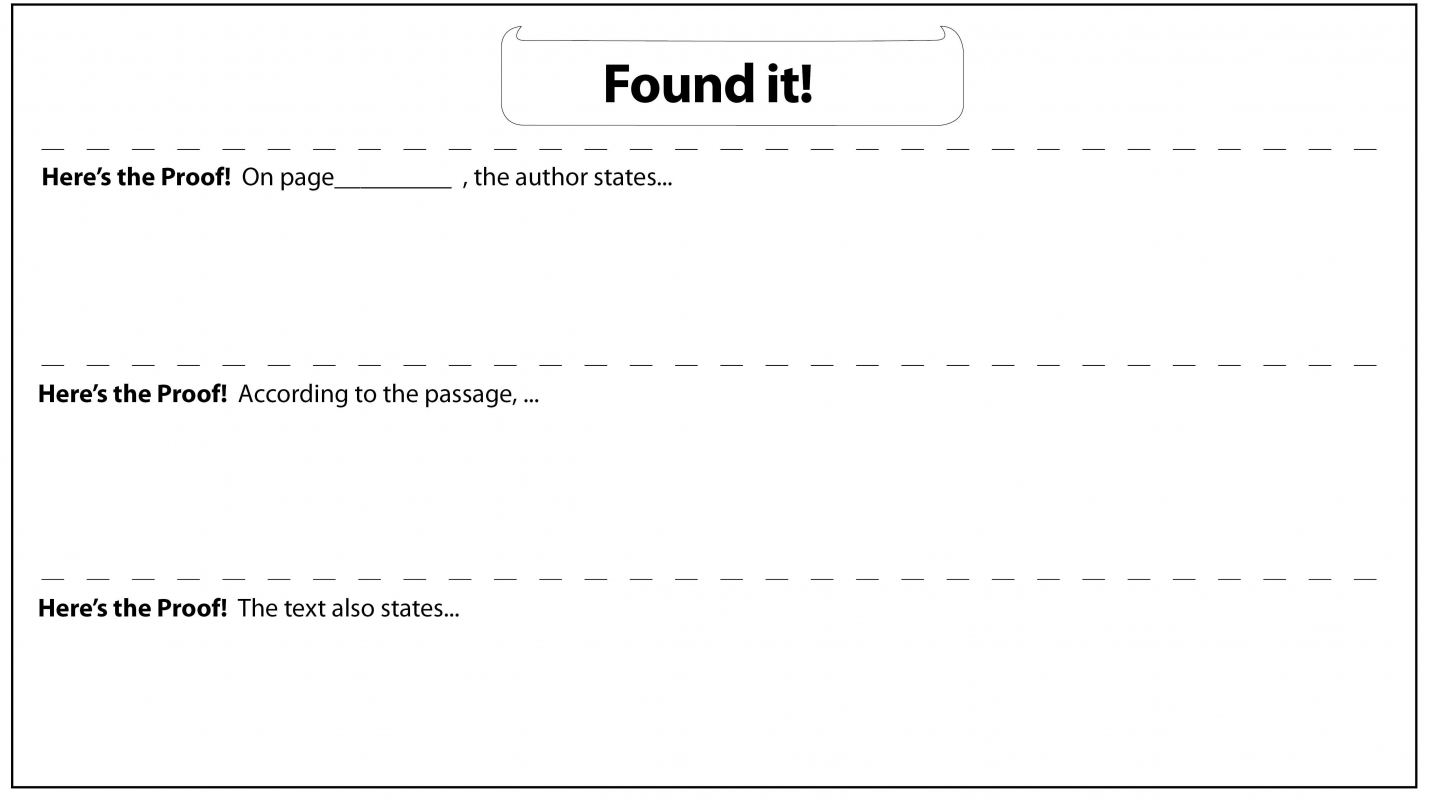

Use the Found-It handout for students to find 2-4 details to support the same question.

If your students are familiar with QAR (Question-Answer-Relationship), then compare the idea of citing multiple details in their responses to the notion of “Think & Search.” They will have to search through much of the text to find more than one supporting detail.

Name

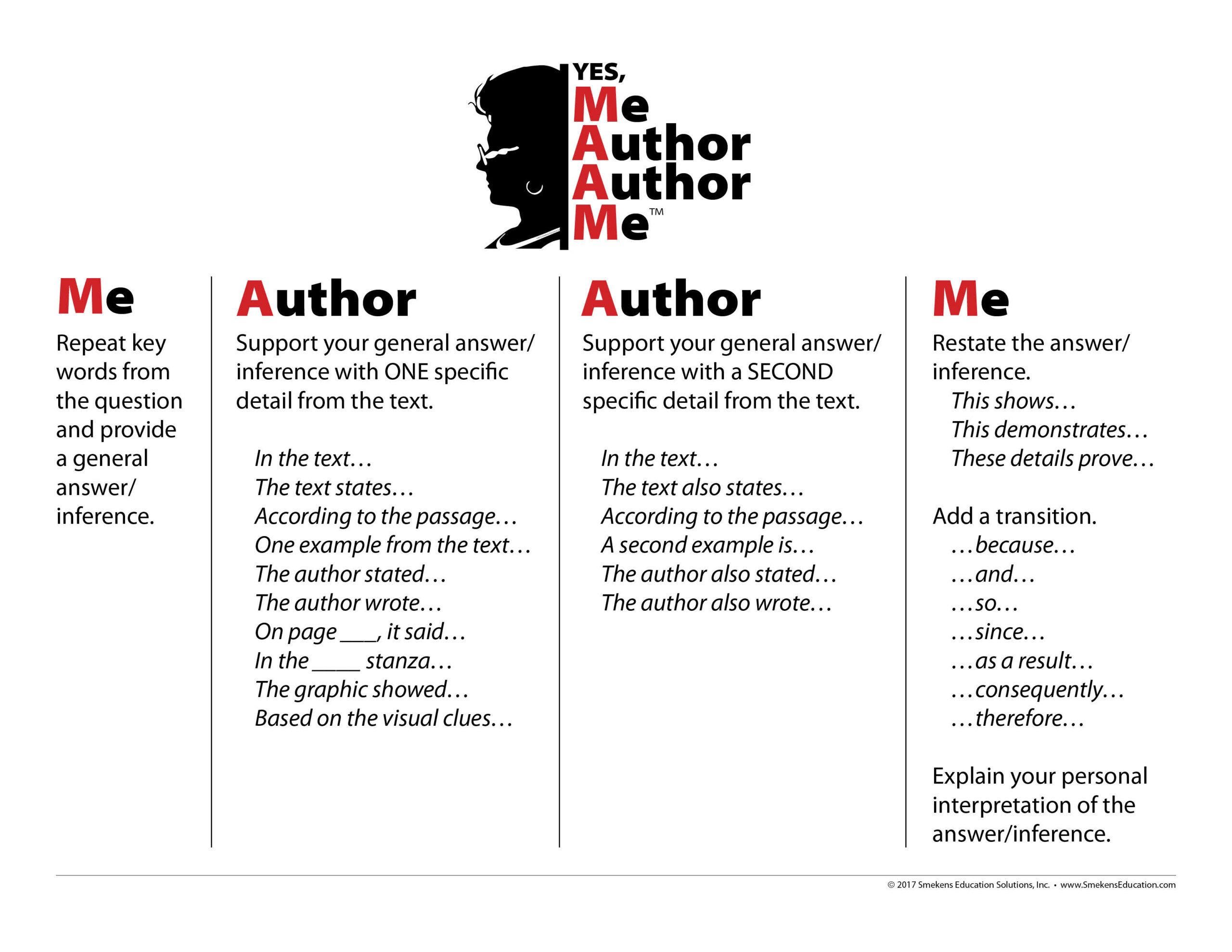

Provide students sentence starters that will help frame their sentences to include the evidence they have found.

Practice this orally before asking students to write any of this down.

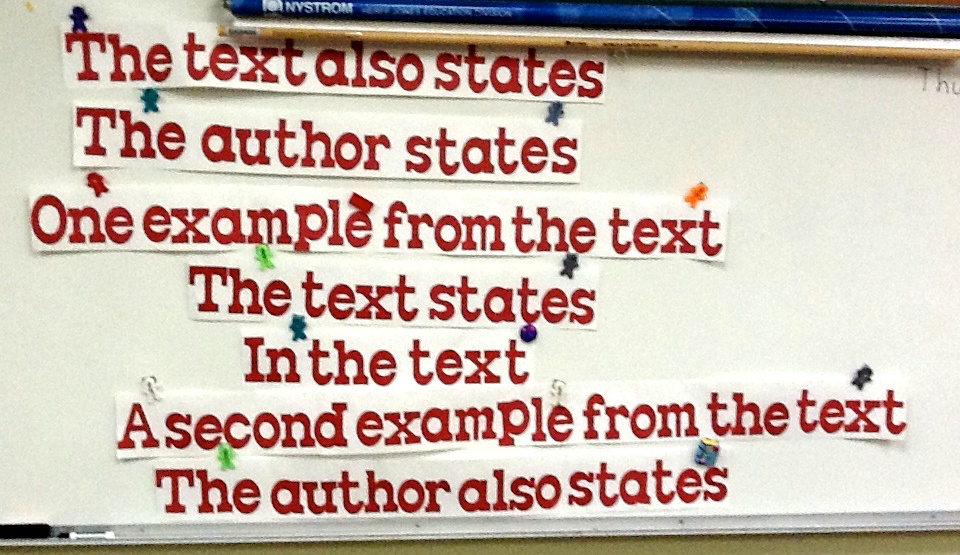

- Crystal Callaway, fourth grade teacher at Bailly Elementary in Chesterton, IN, created XL sentence strips for her white board. What a visual reminder!

- Hold up the mini Yes MA’AM signs to prompt students during class discussions.

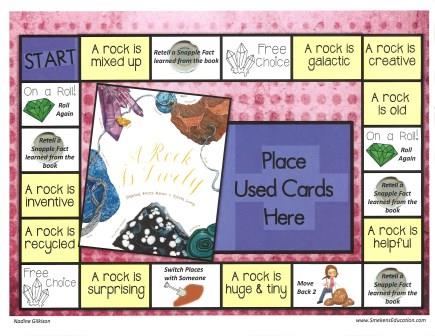

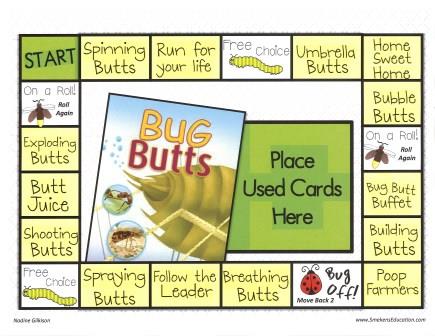

South Creek Elementary teacher Nadine Gilkison provides opportunities to practice referencing specific details while weaving in references to the passage with phrases like According to the author, The text states, and others. Watch the accompanying video for how she uses high-interest informational text and a simple game board to target the skills of text-based evidence. Then download several examples already created.

- Access the game board and sentence starters, plus read student responses for Poop: A Natural History.

- Access the game board and sentence starters, plus read a student response for A Rock is Lively.

- Access the game board and sentence starters for Bug Butts (out of print).

- Use this template to create your own game board for any informational text with section titles or headings.

Cite

Provide explicit instruction on how to weave the what, which, and where details into a textual citation.

Explain

The explanation is a combination of a connection and extension. So first, restate the original inference.

Then, connect the inference to the evidence with a conjunction or transition.

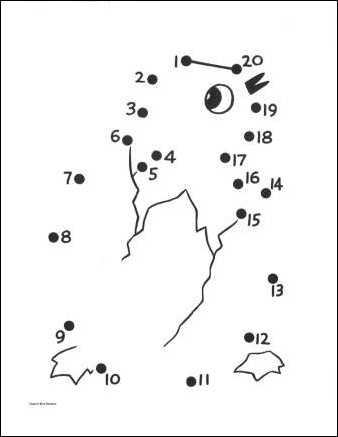

- Compare this step to a connect-the-dots image. The first dot is the inference and the second, third, etc. dots are the evidence. But they must be connected; the conjunction or transition is the connector.

Connect the restated inference to your personal interpretation. Don’t assume the reader gets it. Connect the dots!

Using the Lex Prin video examples, study the MA’AM responses for:

- Staff Bathroom Etiquette—Direct & Honest

- Staff Bathroom Etiquette—Considerate

- Teacher Bumper Numbers

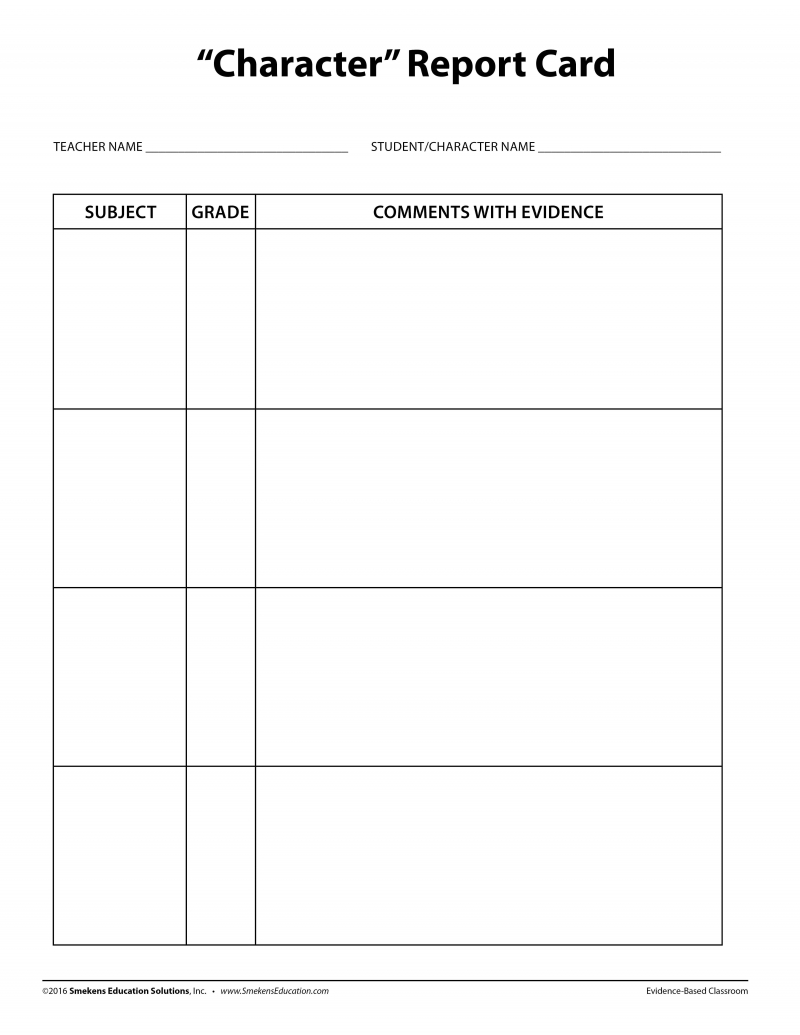

The “Character” Report Card is a great way to practice the explanation side of the constructed response.

- Identify the “character” being assessed (e.g., famous person, literary character, group/organization, society/culture, topic/concept).

- Determine the relevant categories/subjects to assess a character (e.g., loyalty, leadership, wisdom, etc.).

- Students assign a letter grade for each category. (That’s the inference.)

- Then they provide examples/evidence and comments/explanation for why that grade was warranted.

Yes, Ma’am Resources

- Constructed responses require textual evidence.

- Download our newly updated Yes, MA’AM mini-poster.

- Practice writing constructed responses as a class using the Yes MA’AM graphic organizer. (Promethean board or Notebook version available.)

- Then push this formulaic writing structure into small groups for additional practice.

- After practicing the Apples to Apples game to find vital and important details, then have students include that evidence within a written resposne. Knightstown Elementary teacher Kristen Crawford developed a template for students’ Yes MA’AM constructed responses. Notice how she also provided a frame for a strong written response.

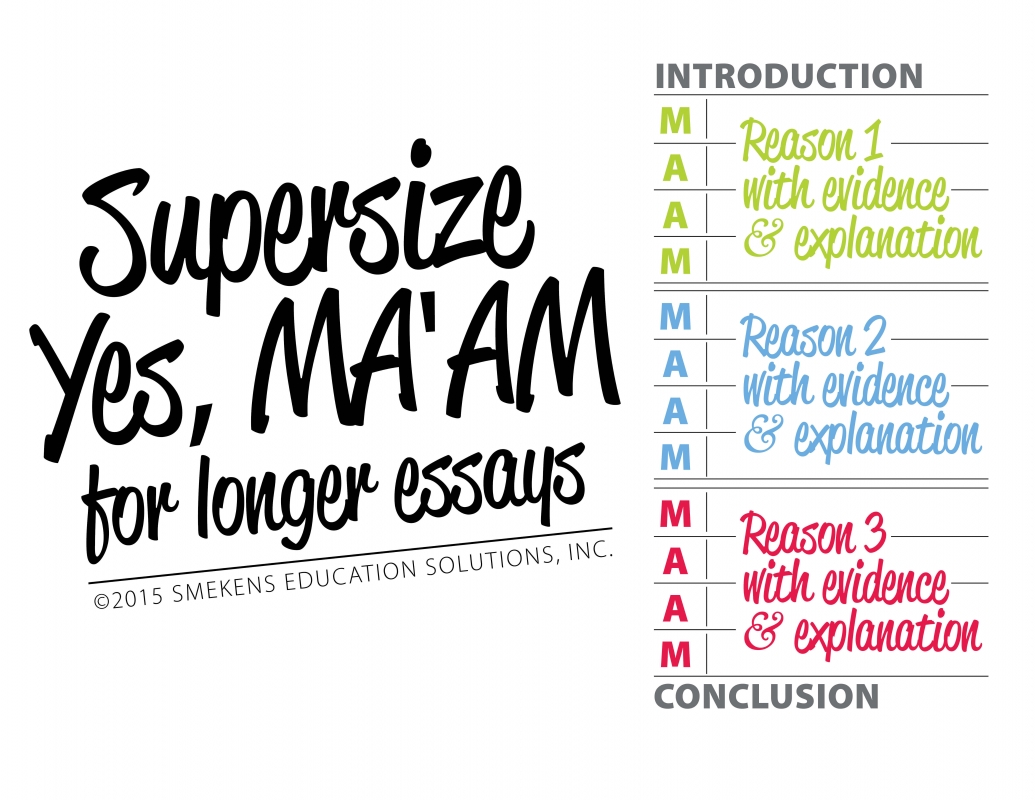

Develop longer, extended responses.

The Yes MA’AM strategy can be adapted to fit the requirements of an extended reading response, as well.