Best-of-Smekens Writing Conference:

Writing Remix 2017

SECRET SITE

SESSION 1

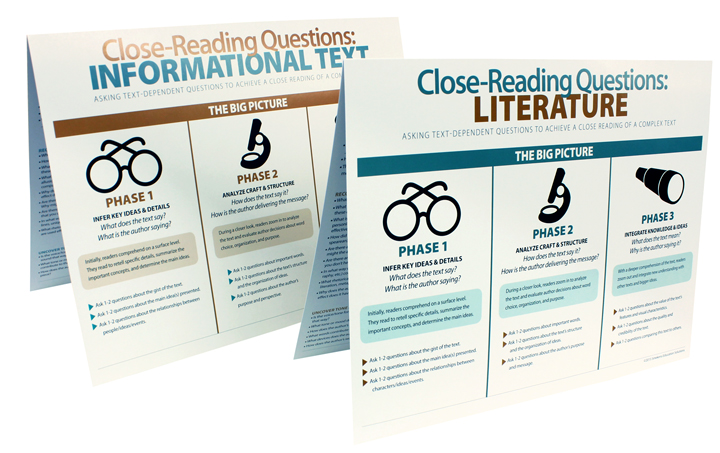

Strengthen Students’ Understanding of Textual Evidence

Create an evidence-rich classroom

To create an evidence-based classroom, the questions teachers ask must be dependent on the text.

Problem #1 Response lacks evidence

Remain neutral when students are giving you their inferences. Don’t “give away” if they are right or wrong. Rather, use a line from the Justification Cheat Sheet to ask them to support their thinking.

Problem #2 Response is NOT rooted in the text(s)

Problem #3 Response just provides details, not evidence

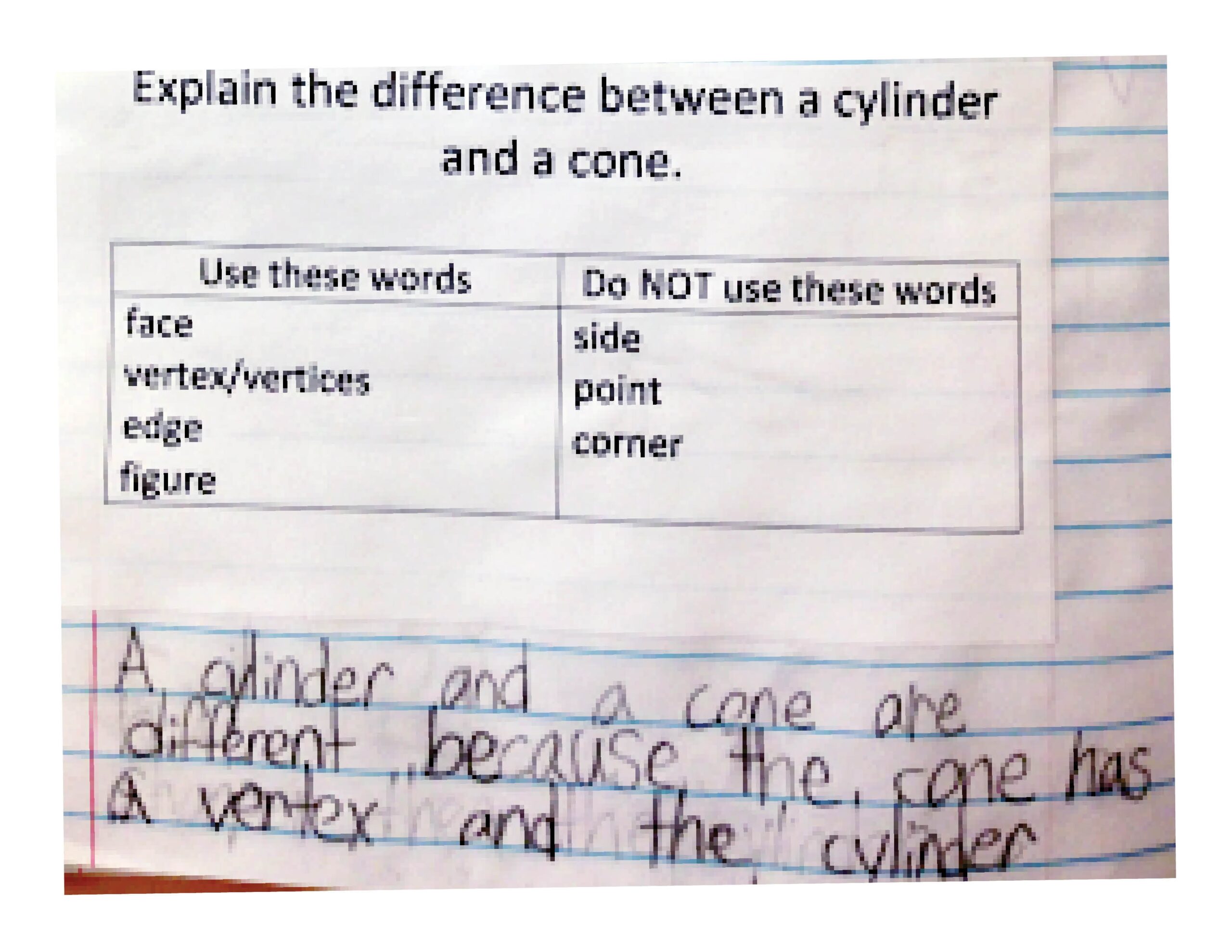

Don’t ask for evidence until you’ve defined it.

Problem #4 Responses lack explanation of the evidence

Text-dependent questions involve the reader making inferences about bigger ideas in the text. Such questions rely on explicit or implicit evidence (SAY) in the text to support a reader thought (MEAN). Download the Say/Mean T Chart as a Word document, PDF document, or Notebook document.

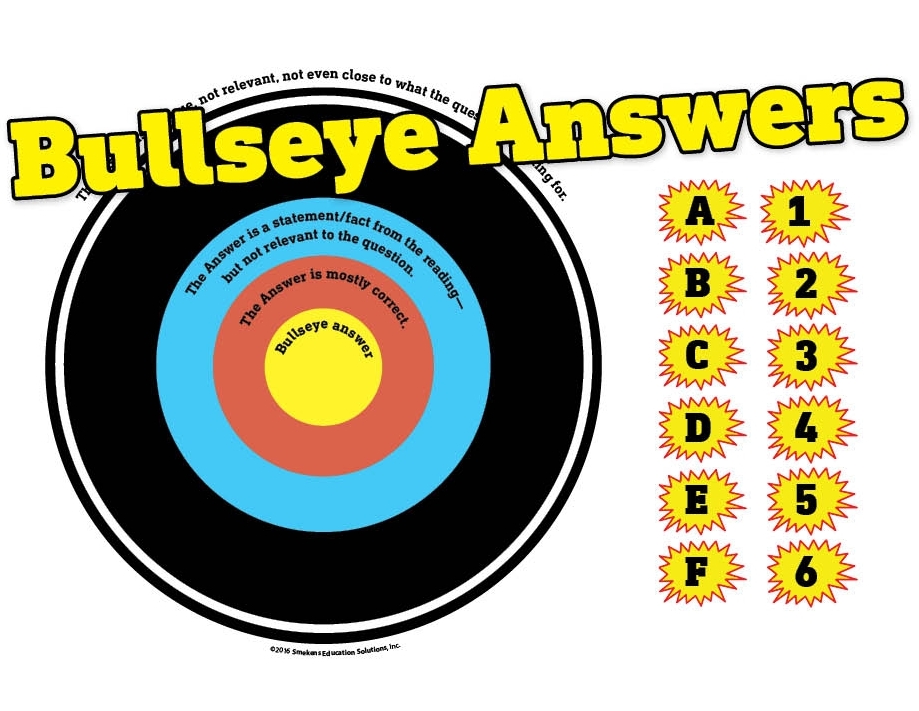

Fine-tune understanding with the Bullseye Strategy

Model how to determine where each multiple-choice answer falls on the bullseye board.

Download a PDF version (Target | Answers)

Download a Smartboard version

Download a Promethean Board version

Access a Google doc for additional practice.

SESSION 2

Identify 3 Types of Write-About-Reading Prompts on Standardized Tests

Narrative Writing Tasks

Literary Analysis Tasks

Evaluate if the movie version stayed true to the original print text.

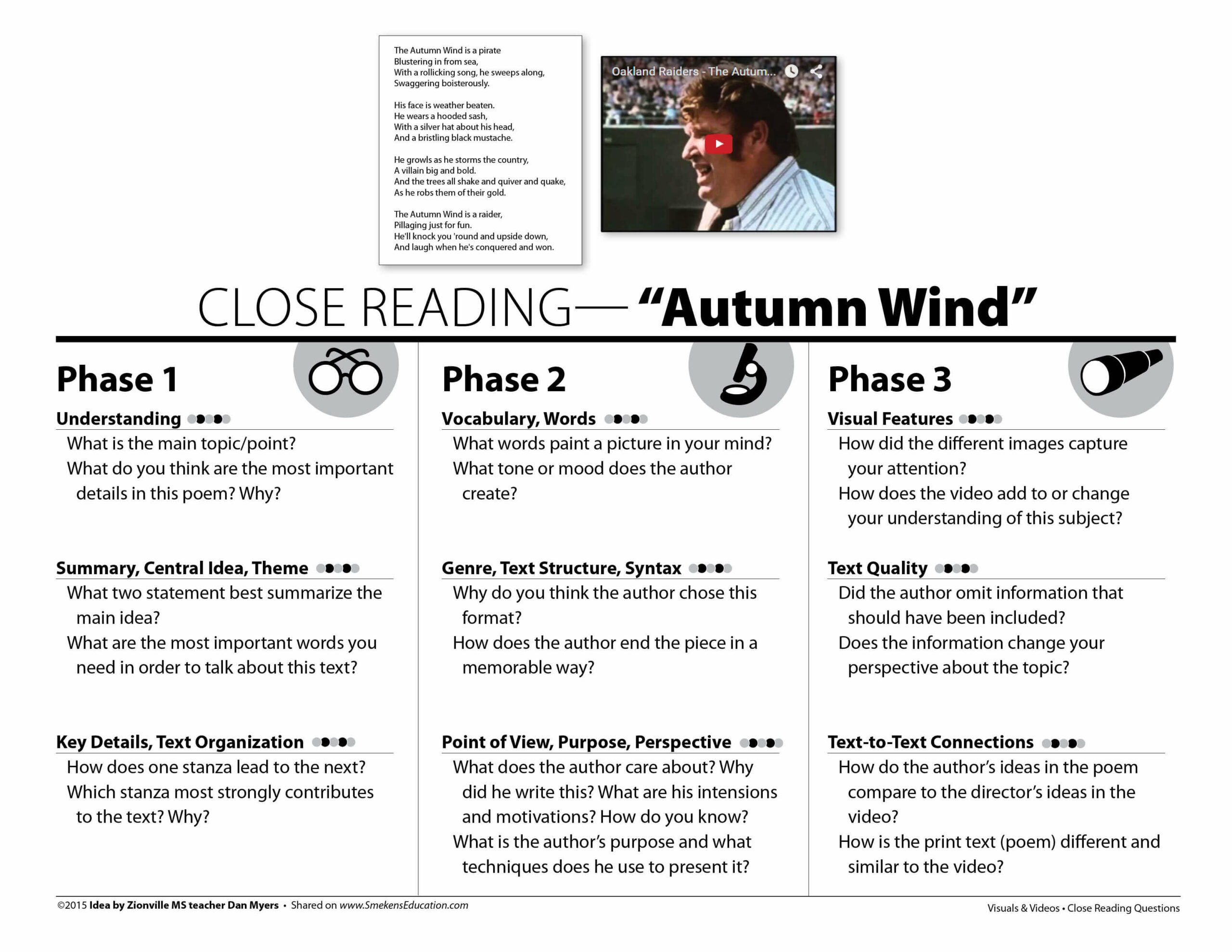

Compare information learned from just the print text versus the visual/multimodal text.

Research Writing Tasks

SESSION 3

Target Constructed-Response Writing

Provide students a consistent formula

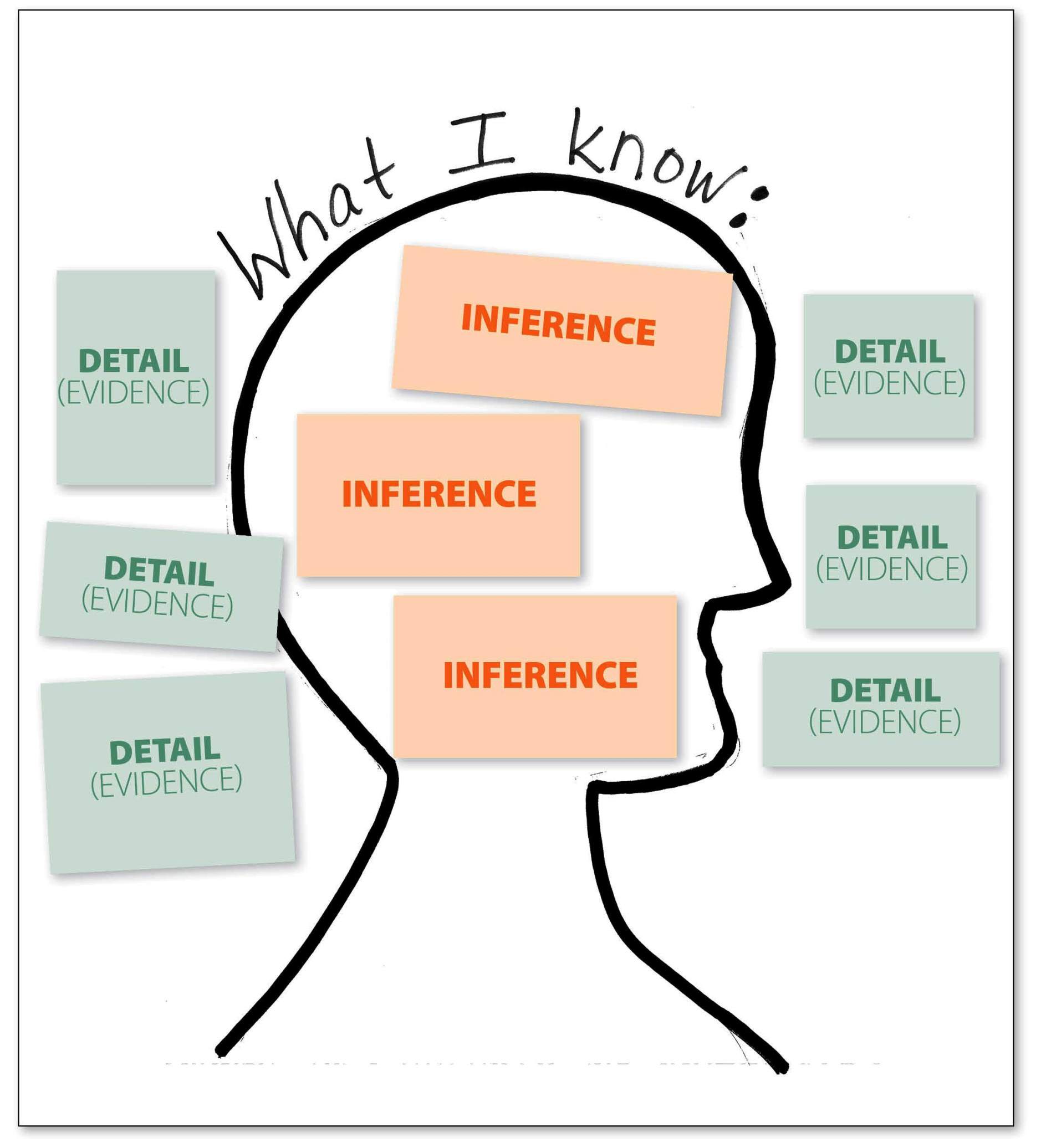

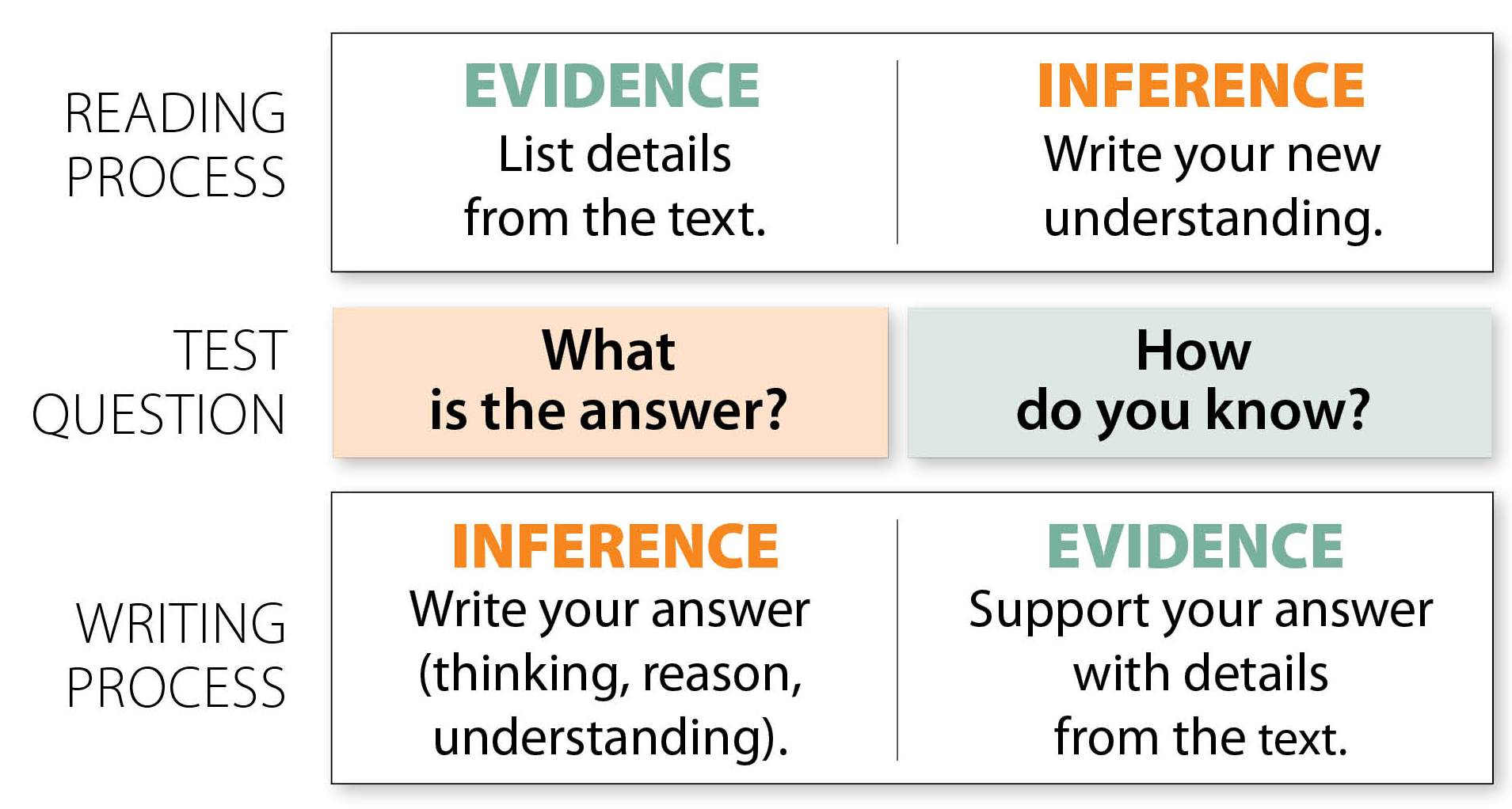

Infer the answer to a constructed response

Break down the process of making an inference into five separate steps.

- Read/View the text.

- Read the question.

- List related details. (Use the silhouette graphic.)

- Look for patterns.

- Determine what they mean.

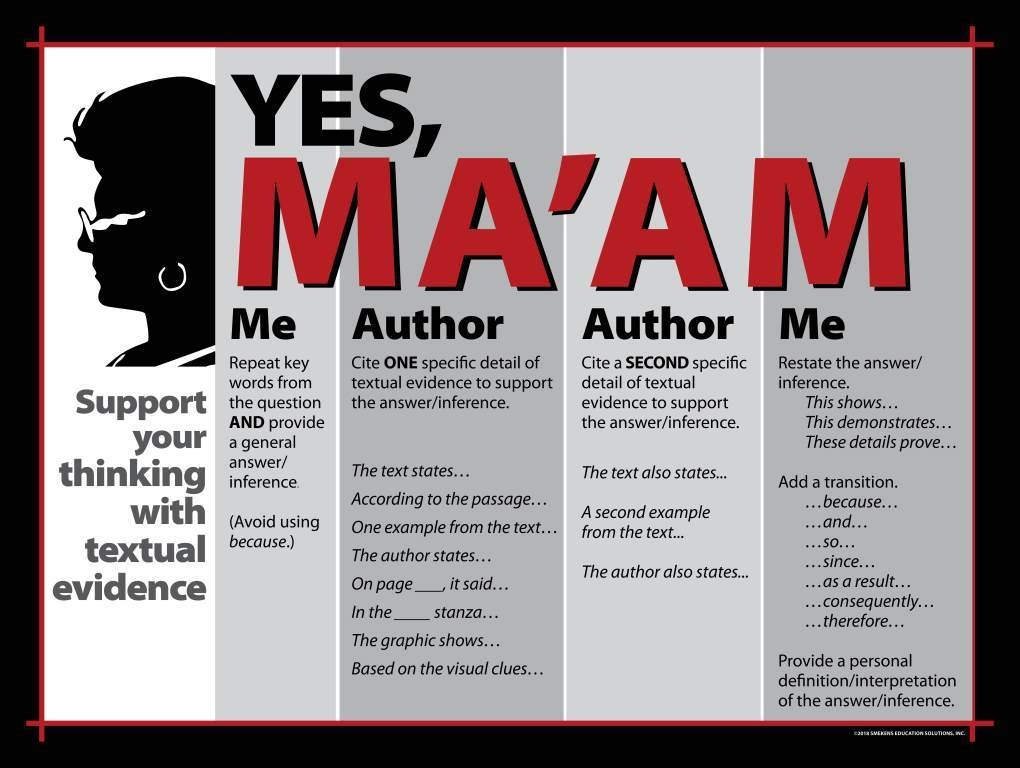

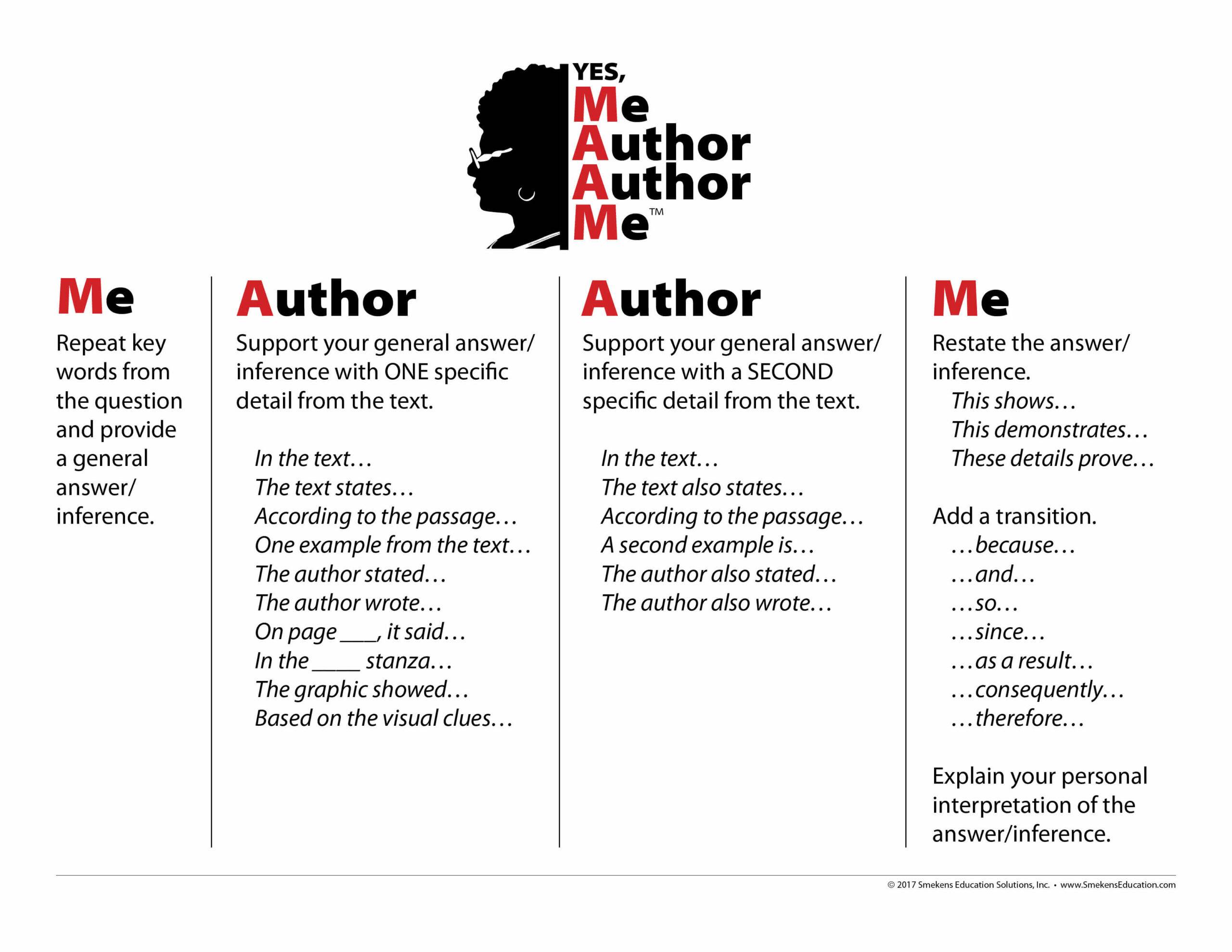

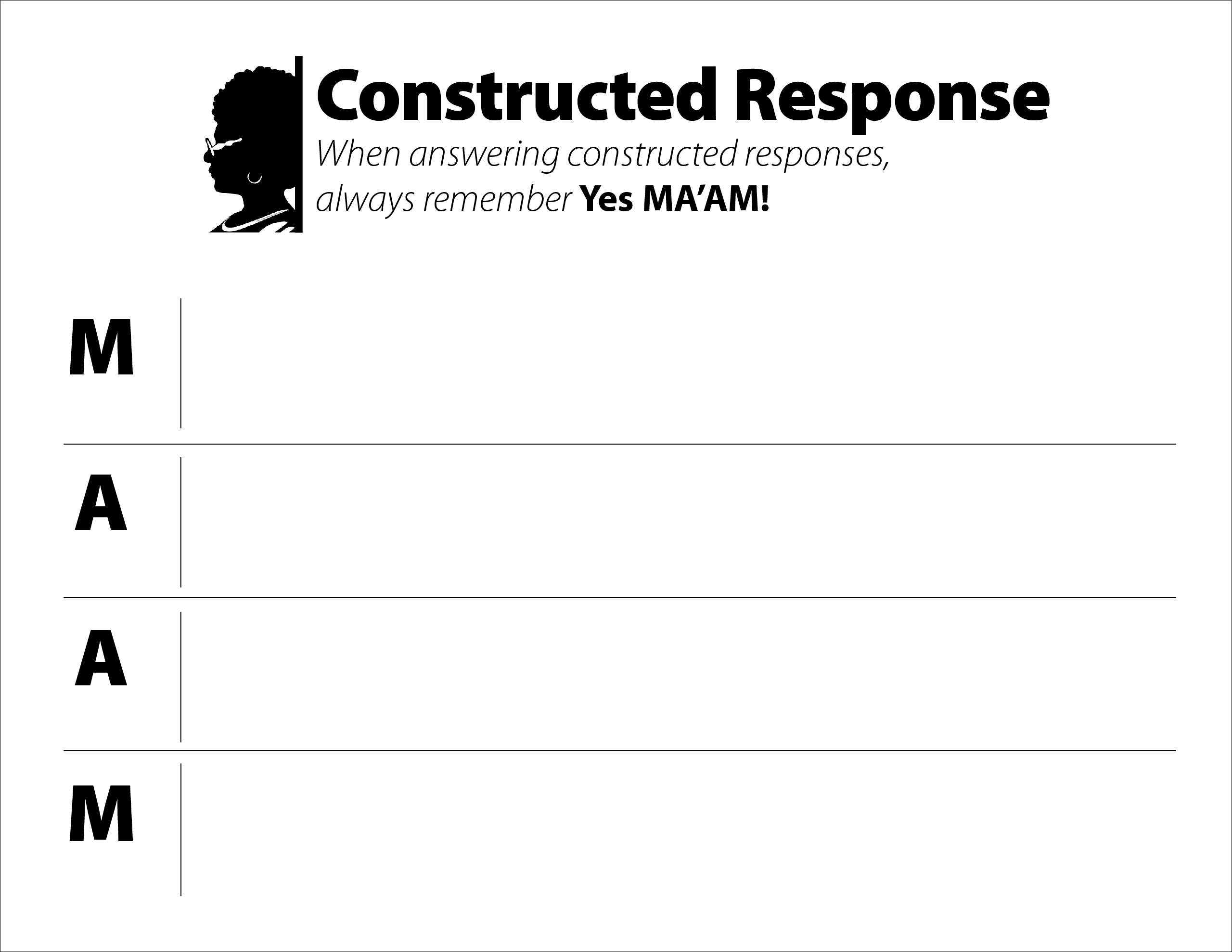

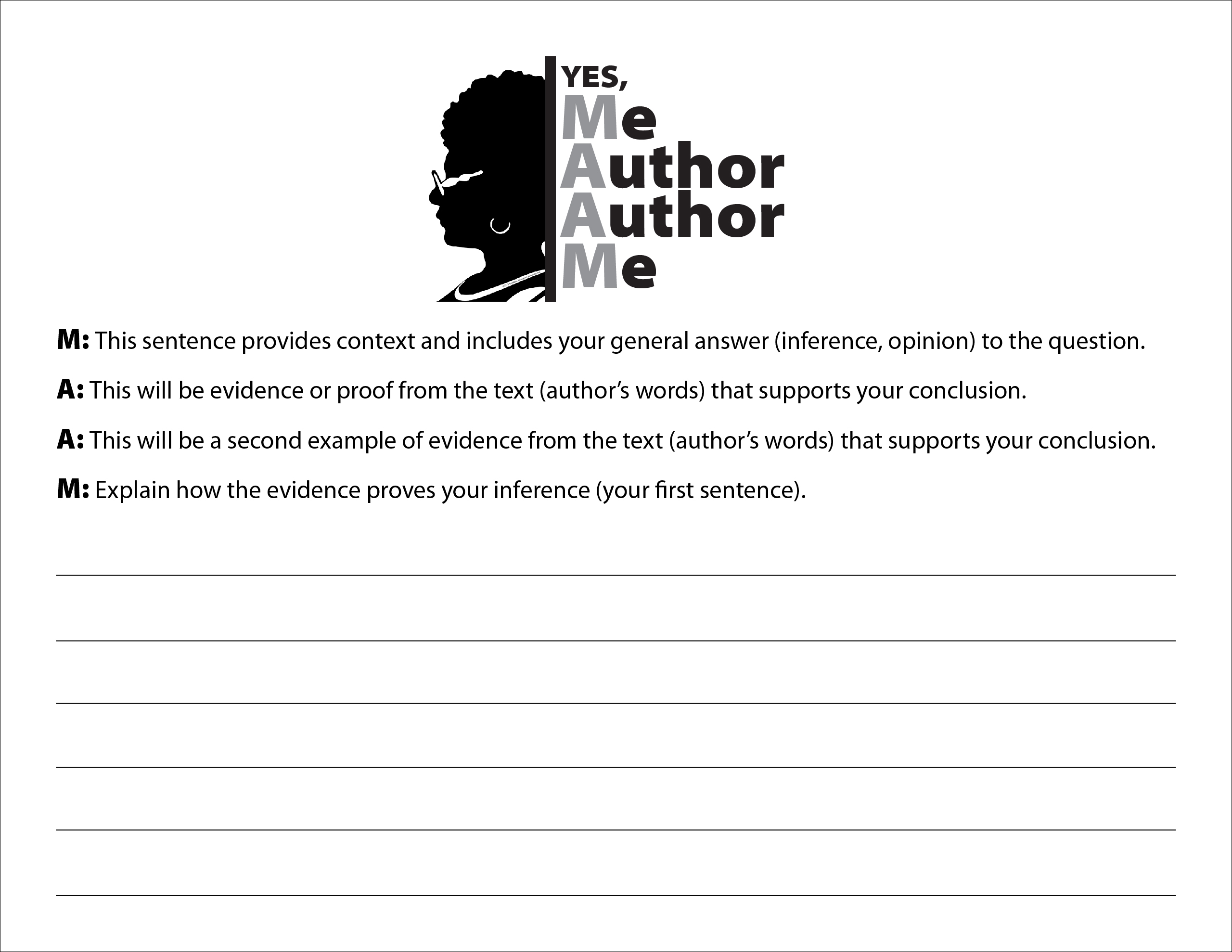

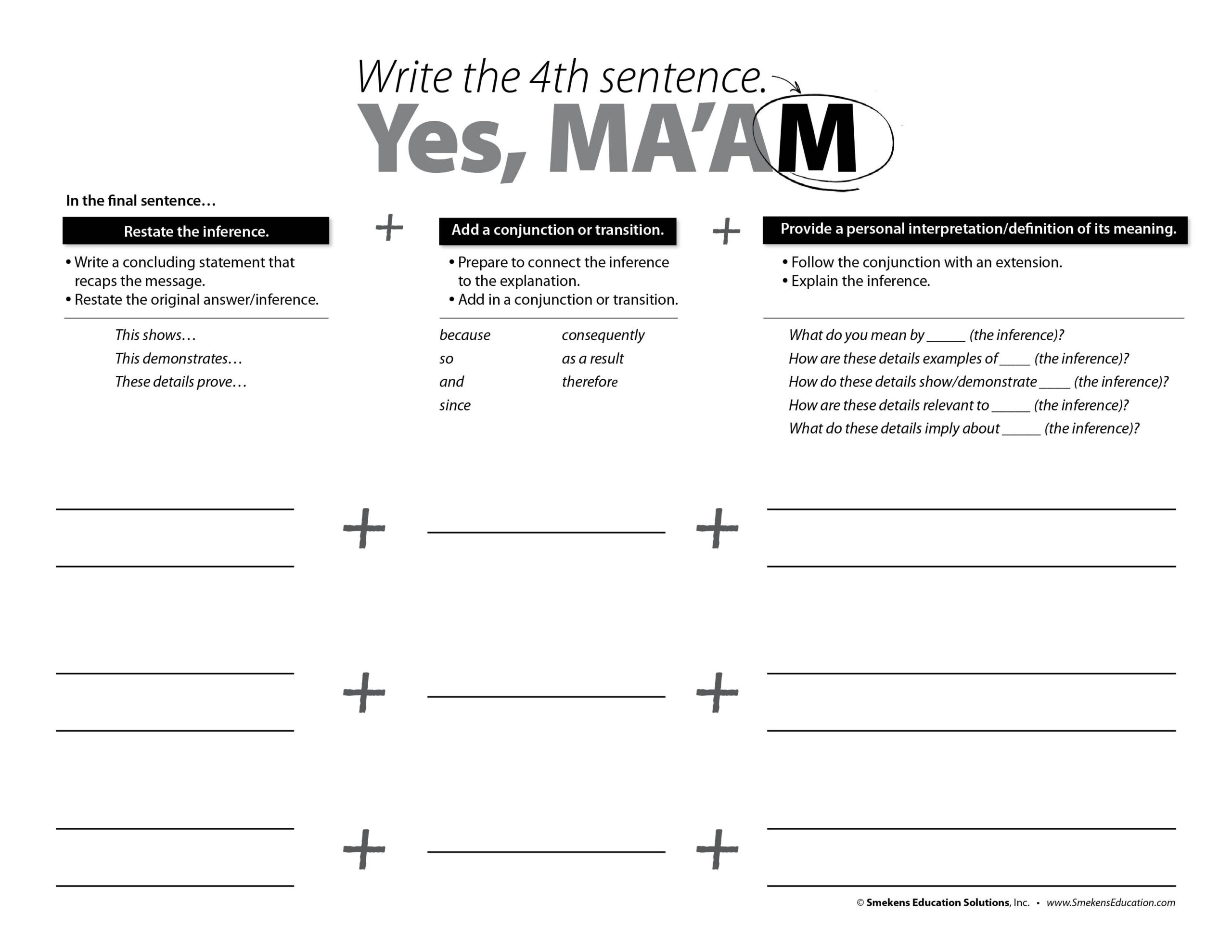

Practice writing Yes, MA’AM responses

Utilize these templates to fine-tune the four-sentence constructed response.

SESSION 4

Demonstrate Content Knowledge through Writing

Target strong first-draft products

The full writing process typically includes multiple days and drafts. However, in the content-area classroom, first drafts are more common with a “Check & Change” in lieu of revision and editing.

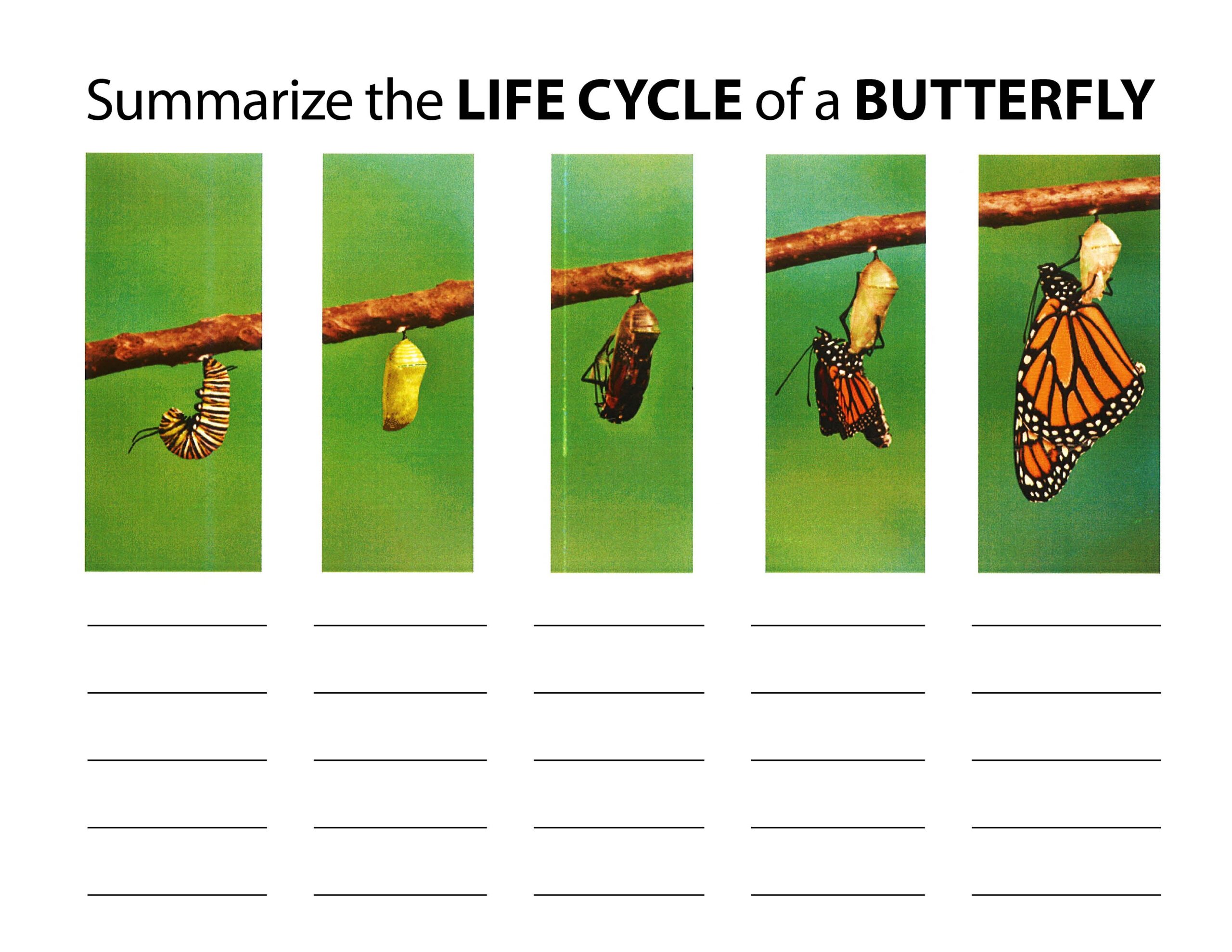

Generate longer summaries

Summaries are condensed retellings. Since they only include the highlights, compare it to ESPN Sports Center.

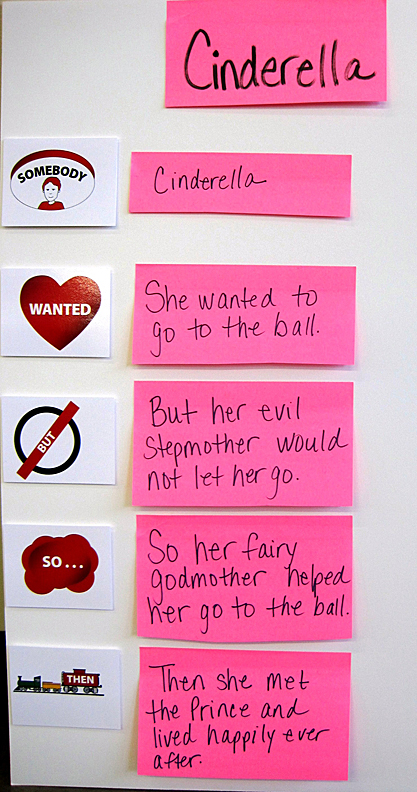

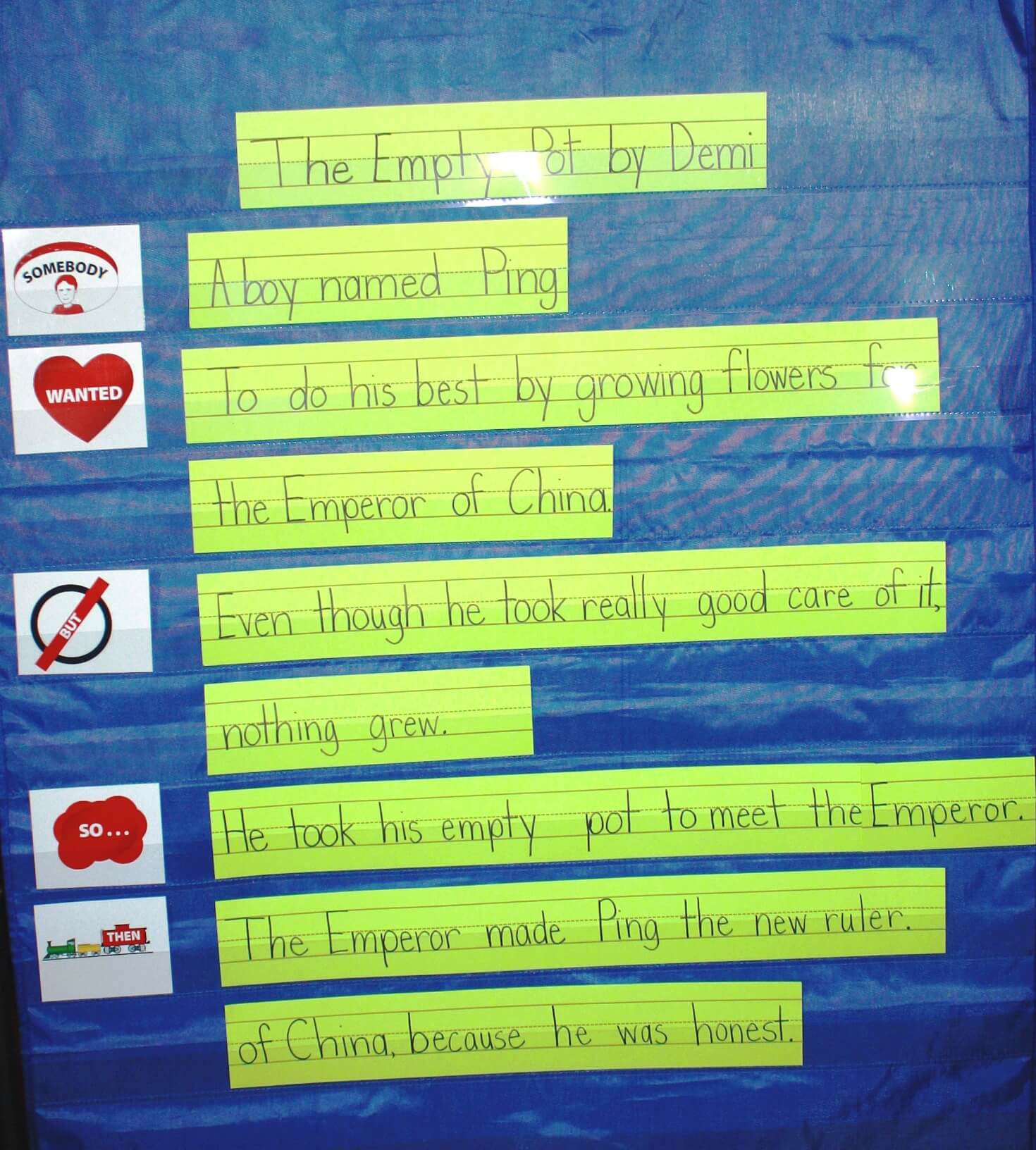

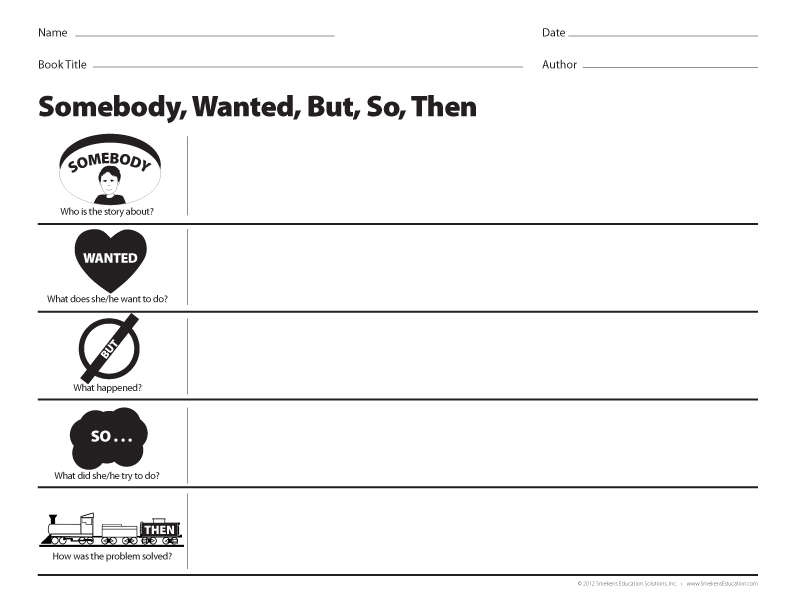

Students can hone their summarizing skills by completing the Somebody… Wanted… But… So… Then… frame.

List and organize information

For longer summaries, provide an ABC Chart for students to list details first. Then, they can logically organize it in one of three ways.

Start with short and powerful writing

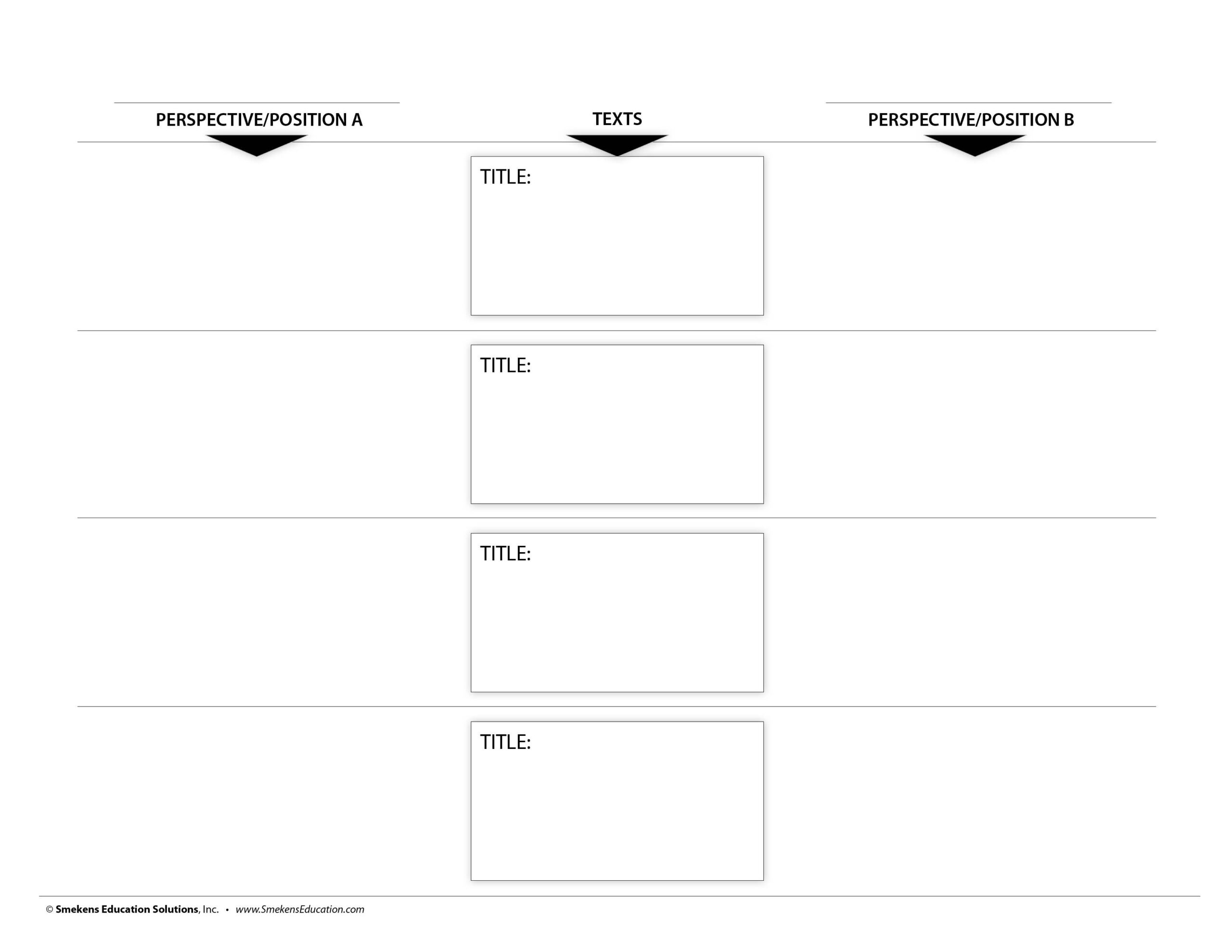

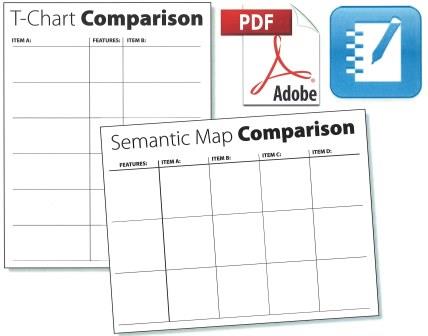

Rather than using the Venn Diagram, introduce students to the more user-friendly 2-column T-Chart and the 3+ column T-Chart. (NOTE: After the template page within each of these downloads, you will find several examples already made.) Notebook versions of both the 2-column T-Chart and the 3+Column T-Chart are available, too. A favorite chart of chemistry teachers is this semantic map that outlines substances, properties, processes, and interactions.

SESSION 5

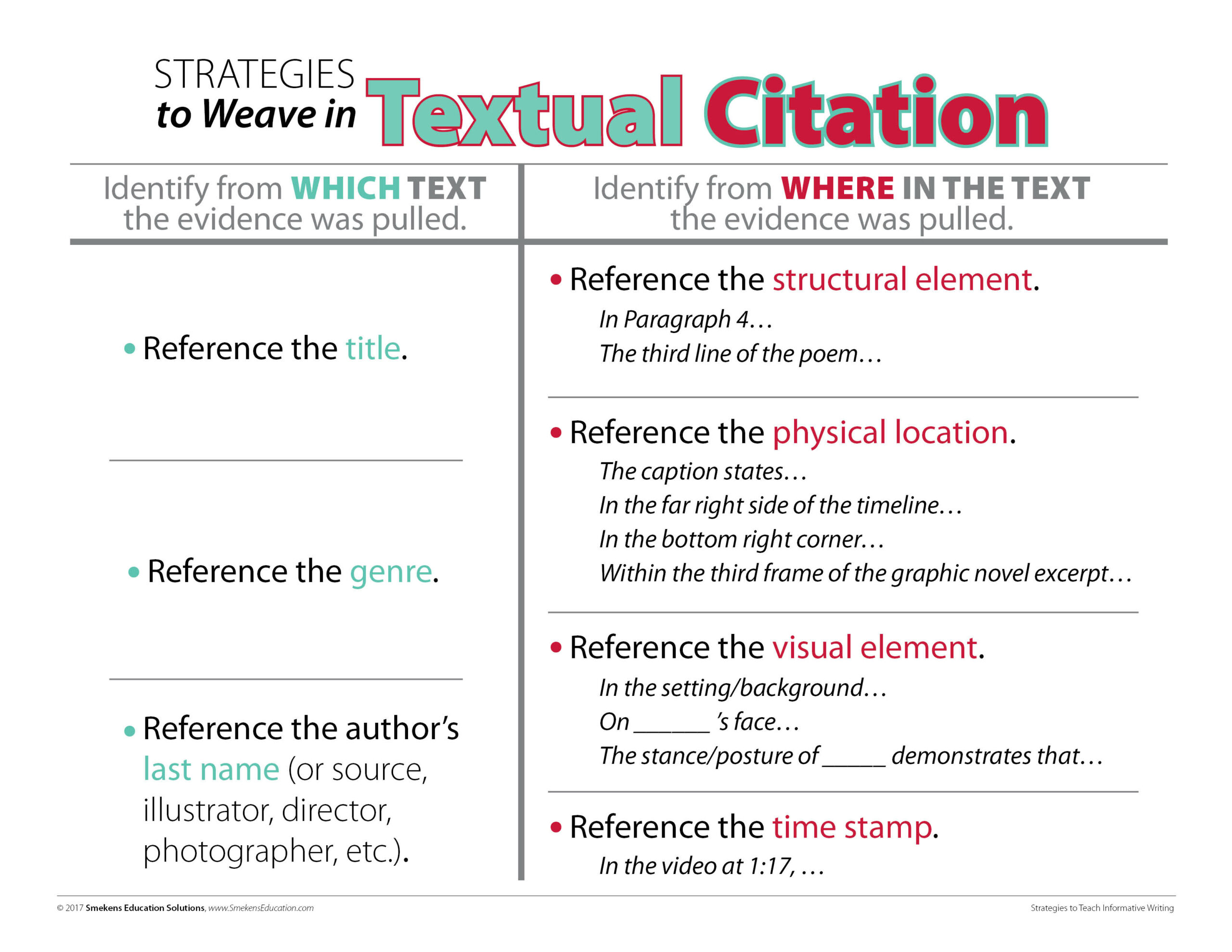

Refine the Definition of Textual Evidence

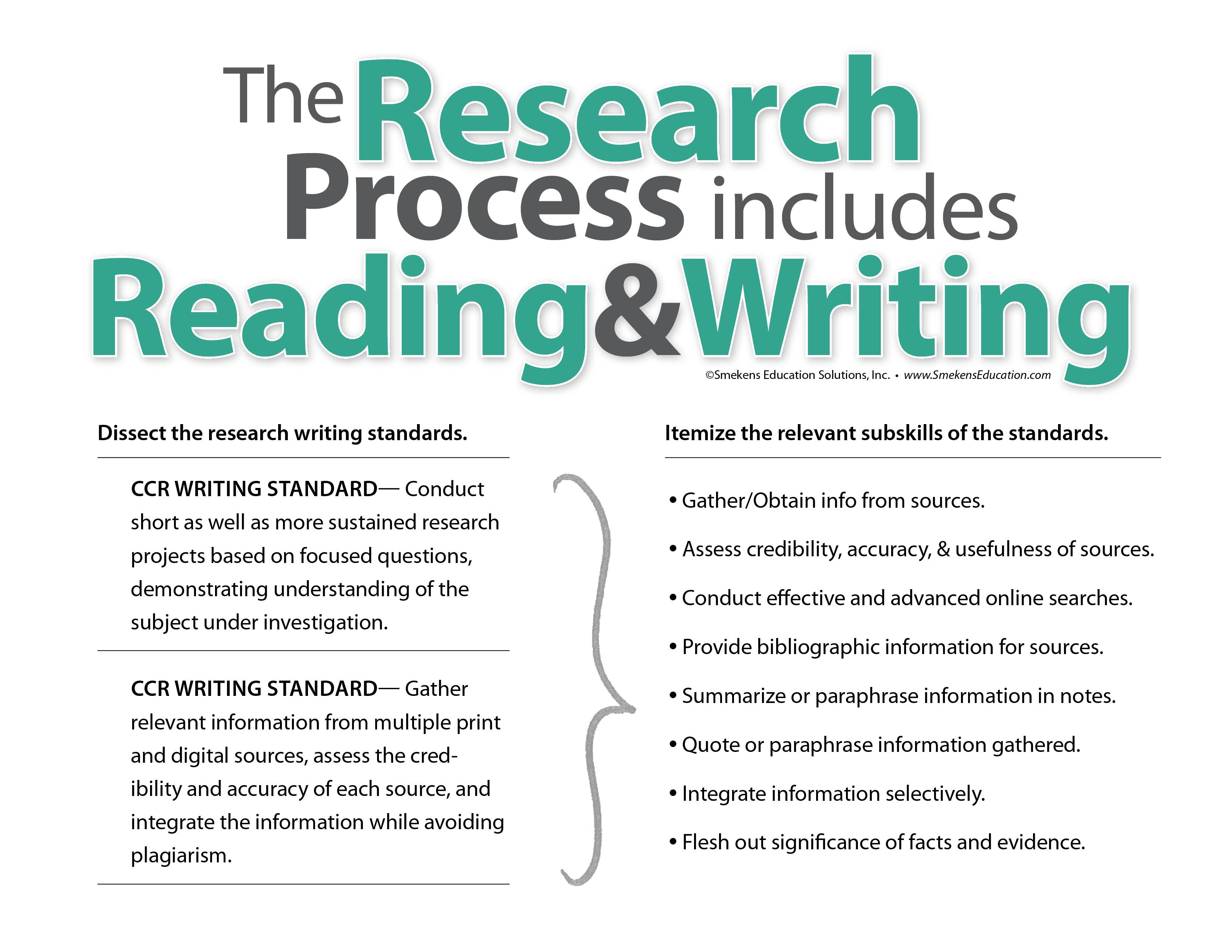

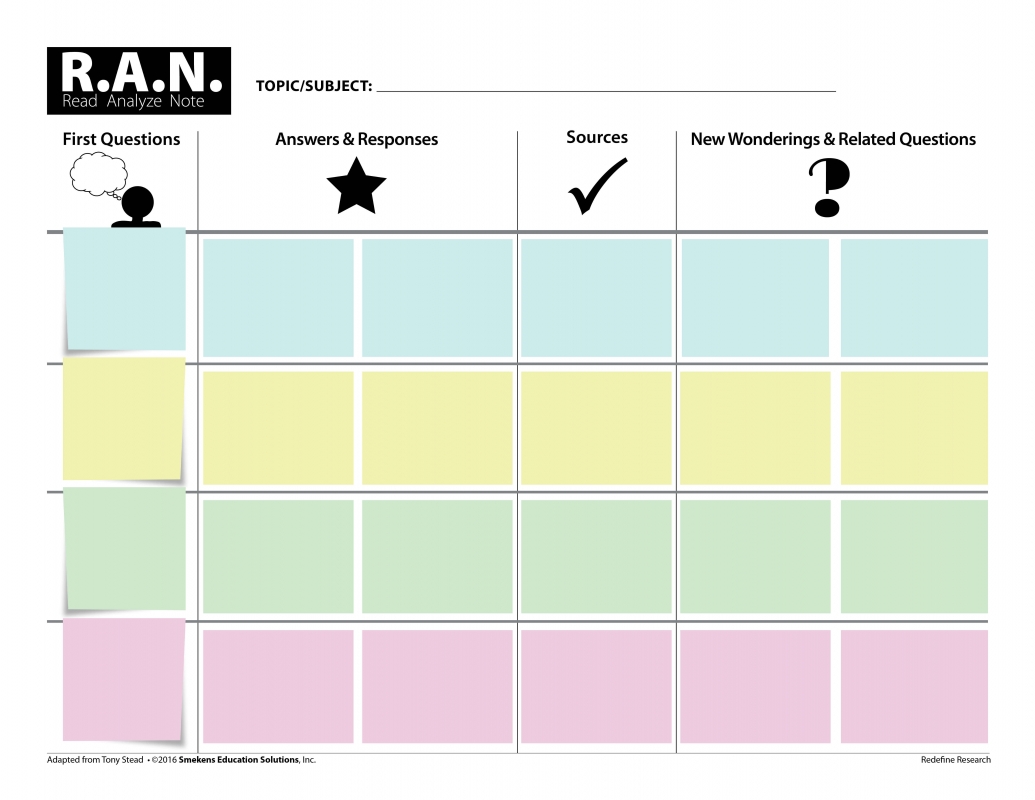

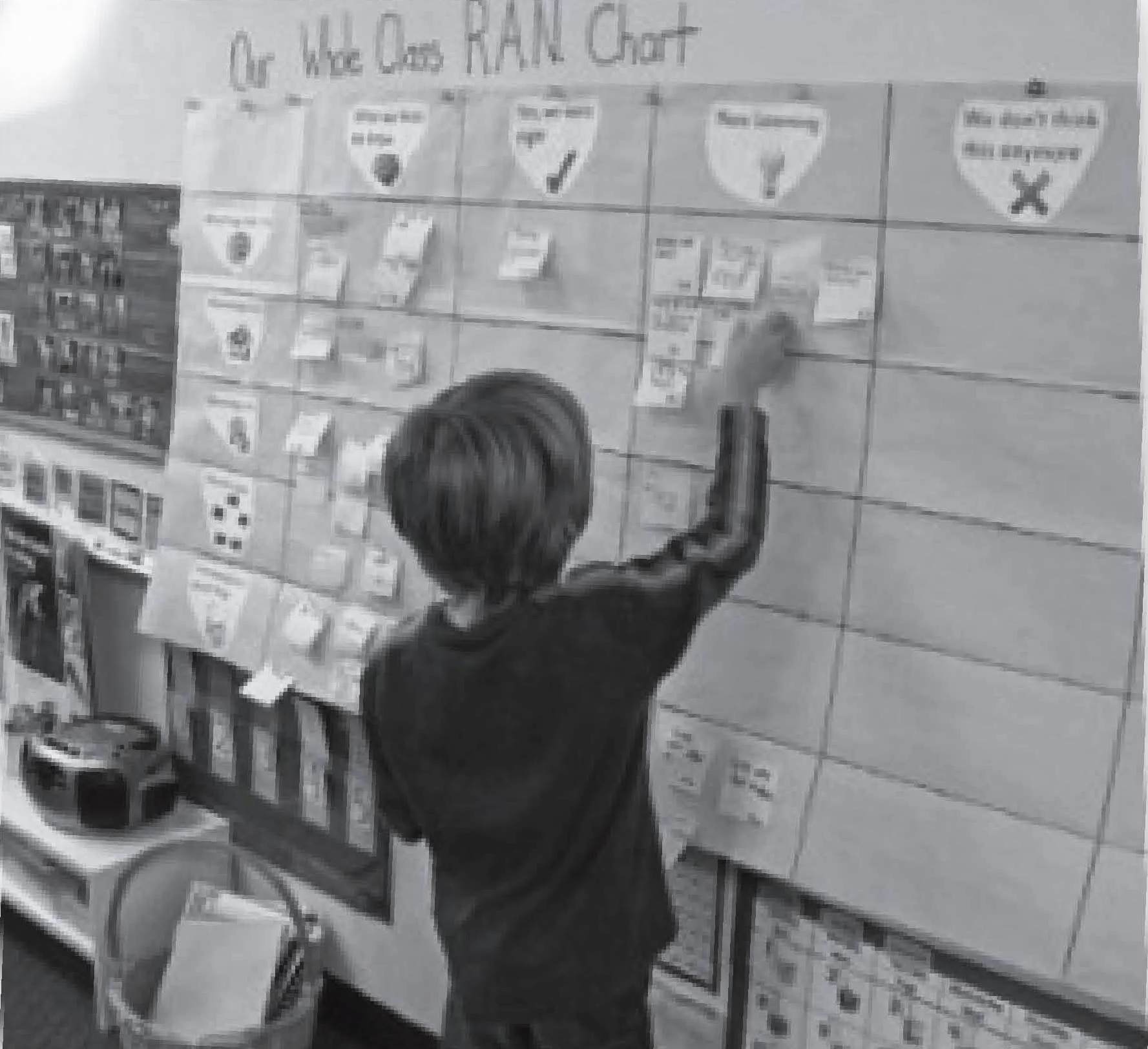

Target reading and writing skills

Simply restating information collected is like the black and white pages of the Fun Magic Coloring Book. But when students add inferences, conclusions, and really flesh out the significance of the facts and information, then their writing comes alive with color.

Gather information from relevant sources

- The online Hemingway Library (or HELios) website offers a great PowerPoint of advanced-searching techniques.

- For advanced searching with Google specifically, this article will be powerful.

Redefine research-writing products

Keep the emphasis on the research process not the product. Look for frequent opportunities for students to generate smaller, faster research products.

1-Sentence-equivalent formats

- The Q&A format allows students to dabble with report writing without requiring a long introduction, logical transitions, and a solid conclusion.

- Information Equations were an idea inspired by Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s book This Plus That: Life’s Little Equations. New understanding can be conveyed through informative equations or argumentative ones.

- Capture the entire topic in a clever tweet. Have students create social media posts from the perspective of historical figures.

- Creating a single PPT slide of researched information includes the opportunity to dabble with the research process and teach some technology standards. If students each create one PPT slide on a common topic, then the slides could be combined into an all-class product.

List-equivalent formats

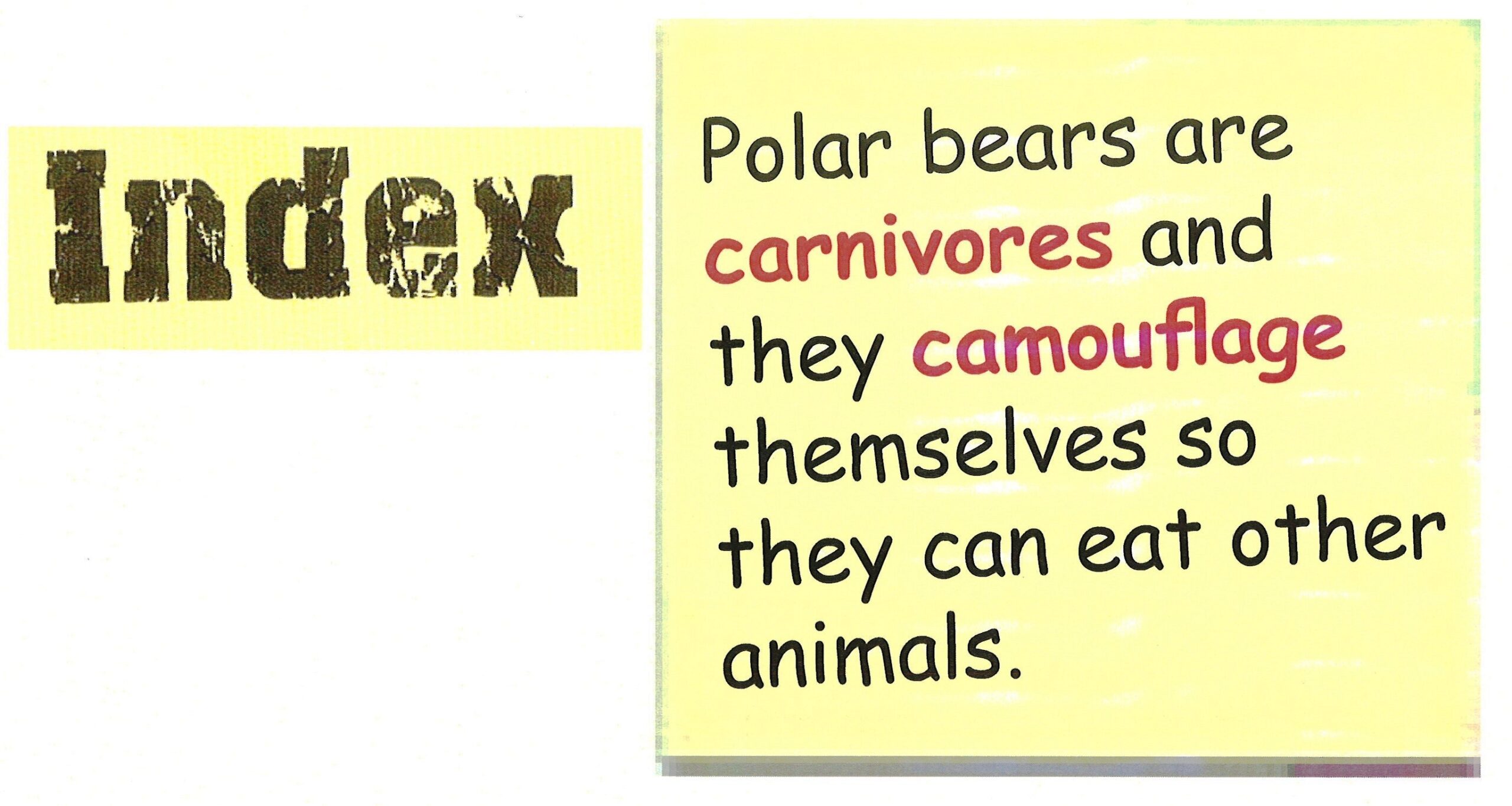

- Labeled diagrams can include the students sketching the visual and labeling the parts. Or, you could provide the visual for them to label only.

- When working on how-to procedural writing, start with a picture series that requires students to write captions. This again allows them to focus on the information in the body of the writing and to ignore the need for an introduction and conclusion.

- It will take serious synthesizing to create a “recipe” about a concept. (Here’s one more example; this one by a high school student after studying the 1960s.)

- A list might not include only straight-up information but also the differing perspectives in a two-column chart.

- Whether as a class or individually, primary students can list out related words associated with a researched topic in the form of an ABC list. To make this more challenging, have older students make a list of key words (e.g., concepts, people, places, events, things, etc.) associated with the topic. Then, following the pattern set in Q is for Duck, they create a complex ABC Book.

Paragraph-equivalent formats

- Create mini-posters with the researched information. Add QR codes for a tech-piece, too.

- Generate informative poems based on the content.

- Mini-books offer a “small” alternative to research writing.

- Young writers can start to juggle compare-contrast thinking with a flapbook.

- Pair up primary students to develop one page of an all-class big book. Again, this allows students to experience the mode of writing without the pressure of creating an entire piece individually.

- Especially appropriate when researching biographies, students could create a short obituary or epitaph.

1-Page-equivalent formats

- A more involved foldable would be a valuable format for presenting information that is multi-faceted. A favorite is the layered book. Here is one teacher’s categories for the American Revolution.

- Printing a PowerPoint document in “handout” format allows students to create a fact flipper (PPT example).

- Using what they know about the topic, they could “interview the concept.” This would include a list of questions by someone unfamiliar with the topic and “answers” from the perspective of the topic.

- This article reveals 5 more short-research options that all include digital products.

Multi-Page-equivalent formats

- Consider a nontraditional research paper—the multigenre-research project.

- Oral presentations of three or more minutes are an alternative to writing a long paper. For a biography unit, this might culminate with a Wax Museum.